|

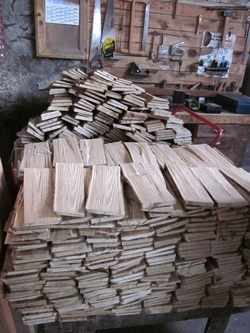

Mark's French Reflection from February 19, 2011 - We’d planned to meet around 10 am Saturday morning and assess the plan for the day. I got up and grabbed a croissant from the bakery up the road. I hadn’t been back long before Michael and Tom arrived with exciting news. His friend Edward had been able to secure a guided visit at a nearby factory that produces chestnut shakes (wooden shingles - bardeau in French). We had been planning to go there Friday but the timing didn’t quite work, so I was eager to learn we’d still be able to make this promising visit work. We drove to Michael’s friend Edward’s house where we picked him up, and he proceeded drove us to our destination. Another British ex-pat, Edward and his wife had moved to France after retirement. Edward was an English teacher at a high school in the Manchester area, is fluent in French and is quite a character to boot. It was only about fifteen minutes by car before we’d arrived at the ‘factory’ and were greeted by the owner Joel Richard (there should be an ‘um-laude’ in there somewhere - it’s pronounced ‘jho-elle’) - a patient, robust man, with a slow, calm way of speaking, a thin mustache and a passion for the work he does. We spent the first half hour or so in the office with Joel giving us an overview of the factory, their products and their process, and us asking questions via Edward to come to a better understanding of the history and background of their business. Joel told us that with the exception of a few companies producing western red cedar shakes in western Canada, they are the only company he knows of that are doing this work by hand in Europe. (and beyond). I initially wasn’t sure if we were going to see shingles produced by sawing or those made by splitting and was now absolutely excited to see their process. (Check out their website at http://www.bardeauxfendus-richard.com/produits_realisations.htm) Joel said that chestnut shakes’ lifespan can vary considerably based on the application and context - the flatter the roof, the shorter they last - but it could be anywhere from 50-100 years. Later in the tour he showed us shakes that had been exposed for 35, 50 and 100 years and it was very enlightening to see how they’d weathered. They charge 55 Euros (about $72 or so) for one square meter’s worth of shakes. They are cut to a consistent length but their width varies a bit. On average, a worker can produce between 250 and 300 shakes in an hour by hand. He has 10 employees and the their retention time is astonishing. The oldest has been there 35 years and the most recent, 15. He said rather comically, people don't leave the business because they want to, they leave because they have to (like, they get fired). When it comes to taking on new blood, if they haven’t gotten the hang of the process in about four hours, he sends them on their way. You can tell if someone will pick it up pretty early on. Joel bought the business in 1956. It had already been active for some time by then. What amazed me most about it was that that meant that he’d been at it for almost 55 years. I would’ve placed him about his mid- to late 60s based on his apparent physical health. To have purchased and taken over a business, he must’ve been at least into his 20s. So he was really much closer to 80. I later learned that the French have one of the longest lifespans in the world (if you don’t account for the young folks killed in driving accidents) - their mandatory 35 hour work week and philosophy on the work’s role in life likely helps support it. They source the wood they use for their products from about a 12 mile radius. They typically buy the rights to the standing timber on a property - just like things were done in many of these countries traditionally. There’s no problem finding quality wood - it’s abundant in the area. In addition to their ten employees they retain 2 teams of two who do their cutting and raw material procurement. Joel said the ideal log is about 6” in diameter. Larger diameter wood often is more prone to wind damage (or wind shake - a delamination along the growth rings of the tree caused by excessive exposure to wind). He also said that as chestnut matures it tends to warp and twist more. About 70% of the total wood they cut for shakes is too poor quality to use for shakes. Fortunately, there’s no waste, as they also deal firewood and kindling. Thus, their by-products are still a useful value-added product. The shakes are installed while still green. As many of you likely know, wood shrinks differentially in each of it’s three planes. Longitudinally, the shrinkage is negligible - like 0.1% so that really makes no different. But depending on the species, wood will shrink between 3-6% along its radial plane and 8-10% or so across the plane of the growth rings. While this knowledge is valuable, it really doesn’t matter for the shake installer because of the simple fact that wood is ‘hygroscopic’ - it fluctuates in its moisture content with changes in relative humidity. When the air is dry, the moisture content in the wood reaches an equilibrium with its surroundings and it dried accordingly and the reverse is true as well. If they were to only install dried shakes, when the air is humid, the shakes would swell. If they’d butted each shake against one another edge-to-edge, they would buckle. So instead, they stall the shakes green, butting each one up to the next, fully knowing that they’ll shrink over time. The considerable overlap between each row (only about 1/3 of the length of each shake is exposed to the elements) means no water can penetrate the roof. Once the shakes fully shrink and dry, the result is a small gap between each shake that is perfectly sized to accommodate for subsequent swelling during times of high humidity. What a great system! Around this point in the conversation, Joel agreed to bring us into the workshop and show us the operation. With pallets of shingles stacked all around, their scale of their production was clear. In total, they produce 10-12,000 square meters of shakes each year - limited more by demand than their ability to produce them. In addition to roofs for houses, barns and other structures, much of their business comes from organizations devoted to historic preservation, replacing old and worn shakes with new ones. I never found out whether or not they also install their product, but I was led to believe that they simply ‘manufacture’ them. It’s challenging producing a product that has such a long lifespan - in some ways you design yourself out of a job. To stay competitive, they’re also considering marketing their sawn shingles more actively (they do currently produce some), as the bottom line better supports the business economically. That said, they’re not really in it for the money - if they were, they’d be doing something else. They love their work, and it absolutely showed. On the exterior face of the warehouse/workshop, a painting illustrated the vital role chestnut plays in this process. A lone chestnut gives way to a tree which is then coppiced. The next panel features stump sprouts emerging from the cut stool that later grow back into poles. This simple pictograph clearly portrays the elegant cycle. Inside the shop various machines and devices proved a feast for the value-added, craftsperson’s eyes. The first thing I recognized was the impressive shaving horse-like holding-device design. Edward translated it into a ‘goat’ - I’m not sure that that’s technically what they call it. The device is used while standing, rather than sitting as one would do while using a shaving horse. The clamping mechanism features a fabricated steel arm and leg which are tensioned via the action of a heavy spring that keeps the jaws in the open position when not engaged. The wooden base includes several short steel spikes embedded into the surface to help improve the grip. This is a well-engineered tool, perfectly suited to their needs. They also have machinery that can be used to mechanize the process including a mechanical splitter, but Joel demonstrated the traditional process for us. He told us that it would be difficult for machinery to perform any faster than a skilled worker could by hand. Effective work requires a keen eye and an attention to the details of an irregular material that would be difficult to automate. Thus, skilled labor is still a highly valued asset that fortunately can be sustained by the current market value for their products. Joel started off by grabbing a bolt (section of chestnut log) that looked to be high quality. He then picked up a ‘de pert tois’ - or what we would call a ‘froe’ in English. Essentially a long thin wedge with a handle affixed at a right angle. The tool is used for splitting, or riving (or cleaving in the UK) wood in a controlled way. Joel began to systematically reduce the chestnut round into probably about 8 rough split parts. These rough parts really weren’t all that rough - they only required a few seconds of hand work before they were ready. Riven shingles (again ‘shakes’) last longer than their sawn counterparts under most conditions for a few reasons. Firstly, the fibers of the wood haven’t been severed by a saw blade so the cellular structure of the wood isn’t nearly as exposed to water, fungi and other decay organisms. Also, the grain of the wood is running clear through the piece which makes them stronger. And finally, the rough surface of the shakes that comes as a result of the splitting process physically acts like a natural landscape complete with ridges and valleys, channelizing water and directing it away and down the shake more actively. After riving the shakes, he then used a violent-looking relative of the froe, with a curved blade, a razor-sharp edge and a set of teeth carved into the short end of the tool. Joel used it to remove the sapwood from each blank with a hewing motion as one would do with an ax. This was a tool I’d never seen before, and being the traditional craft junkie that I am, I was nearly drooling over it’s clever design and functionality. On the wall, I noticed a gorgeous single bevel (hewing) hatchet with a bulbous handle. It almost looked like something out of a cartoon - I had to ask what it was for. Joelle explained that it is actually used for the same purpose - to hew off the bark and sapwood from the split shakes. He passed it around and told us that the swollen handle base is a clever way of helping balance the tool in use - it acts as a counterweight against the heft of the handle - you could definitely feel it work in your hand. The next step in the process was to taper the shakes so the top end was narrower than the bottom and they would fit onto the roof surface more evenly. As I mentioned earlier, only about 1/3 of the length of each shake actually remains exposed on the roof, so the smooth shaved surface of the shake isn’t exposed directly to the weather. This was a quick process carried out on the ‘goat’ with a razor sharp drawknife. Many of these tools are difficult to come by today. Or if they are available, they are either of inferior quality or expensive to obtain. It was clear that many of their tools had seen considerable use over time, picked up over the course of several decades. While on the goat, Joelle showed us how quickly and easily he could add a chamfer to the bottom edge of a shake, conferring an aesthetic detail to the product. This only adds a small cost to the product at the end of it all. For plain retangular shakes, the process would then be complete. But they do offer more decorative patterns - including rounded and pointed bottoms. To do this, they use a tool whose name escapes me, but it’s one I’d only ever seen before in books. I had associated it with clog makers in northern Europe after having seen it illustrated in John Seymour’s beautiful book - The Forgotten Crafts. The tool features a heavy log base supported by 3 or 4 legs. Three legs are actually easier than four to keep level on uneven surfaces. A heavy, stationary metal ring is affixed to the log base near one edge and then a tool that looks like a heavy-duty machete with a hook at the tip is engaged with the ring so as to lock the tool in place. This essentially fixes one end of the tool and provides the user with considerable leverage to do their shaping work. It also allows them to pivot and control their work remarkably effectively. The use of this tool in action is beautiful to watch. Efficient, graceful and ergonomic, Joel was able to add aesthetic details to each shake in a matter of only a few short seconds. And with that, we’d seen it. A low-tech, highly skilled approach to adding value to a wonderfully, rot-resistant polewood species. After our demonstration was complete, Joel showed us a few more illustrations of some of their work installed, and we chatted a bit more about the process and the economics of their business. They’re staying afloat but they’re definitely not growing was the most concise way to put it. This wonderful man left me feeling inspired by his passion and dedication to this craft and excited to locate or fabricate some of these new tools once I return home. We left the factory feeling almost giddy with excitement - and this was only our first of two stops that day. Edward took us on a short detour through a nearby town on the way home to visit the basilica which featured a roof fashioned from Joel’s shingles. We took a few minutes to explore the interior of this holy house - more than 5 centuries old with it’s massive granite columns and impressive upper dome. We then west to the edge of the village - which lay along an important pilgrimage route that’s existed for hundreds of years, and enjoyed the sweeping views of the surrounding countryside. From there, Edward dropped us back off at our car, we raced home for a quick lunch and then set off towards the south - about an hour’s drive to visit the Chevrier family who have created their business around the management and value-adding to sweet chestnut coppice….

2 Comments

4/12/2020 03:11:02 am

I don't exactly know what the shakes are all about, but I am glad to see that you are enjoying what you do! I know that you have been working so hard for that project. Please know that whatever you are doing, you have our utmost support and we will always be here to cheer for you. I hope that I'll get to know more about you and your work because that's going to be a huge honor for me if ever! I cannot wait for that to come!

Reply

1/23/2024 09:18:49 pm

Jack Listens is a renowned food department store in the United States. To ensure customer satisfaction, they offer a survey where customers can provide valuable feedback. By participating in this survey at https://jacklistenscom.page/, customers have the opportunity to win two Tacos coupons as a token of appreciation. This initiative allows customers to share their experiences while also benefiting from a chance to enjoy delicious food at a discounted price.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed