|

Coppice in the Limosin with Mark part 2 -

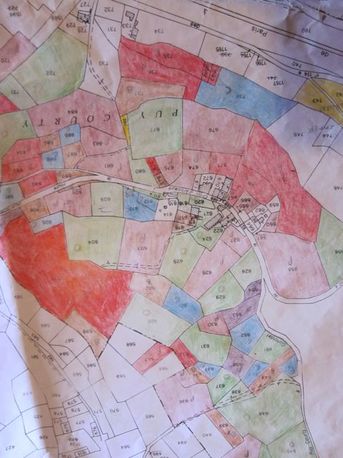

Soon we were back in the car, headed south. Rain seemed imminent on the horizon for much of the day and we hoped it would keep at bay as we anticipated spending at least part of our afternoon outside. The steep hills and wooded countryside of Michael's region gave way to a more flattened series of rolling hills south of the city of Limoges - the largest city in the Limosin region. With signs of suburban sprawl showing along the outskirts of town, we still saw much of the traditional infrastructure and vernacular building traditions displayed with exposed exterior timber frames on several of the structures. Alas, I was unable to snap any photos along the way as we were already late for our meeting. We arrived at the Chevrier’s around 3:15 and entered through the wooden gate unsure of what we might find within. There was little indicator of their craft work evident from the exterior. We knocked at their front door and were soon enough greeted by Serge - the man of the house. He gathered his wife Chantal, met us around the back of the house and proceeded to dazzle us with the depth of their knowledge and dedication to the preservation and perpetuation of these French traditions. (Check out their work on their website - http://accordboischataignier.fr.st/ Hopefully you read French. The photos tell a lot too though.) We had much to cover and not nearly enough time to do it. Unfortunately I never did get a thorough recount of how it was that they came to this lifestyle. We did learn that Chantal - Serge’s wife and a passionate and skilled craftswoman - had grown up in Paris and the two of them had chosen to relocate to the Limosin about 25 years ago. Again reflecting some of the traditions of land ownership, we learned that the Chevrier’s did not own woodland, they bought the rights to harvest the wood on a fixed area each year in the surrounding countryside. There’s no shortage of chestnut coppice in the area, and this arrangement has worked for them to date. For 3-4 year old chestnut coppice it costs about 600 Euros per hectare per year(about $750) and about 1000 Euros ($1360) for more mature stands. Each year they cut one hectare of land to provide the raw materials for all of their production needs. They are typically cutting at the age of 3-4 years, 8 and 12 or so. Of course different sizes of polewood are useful for different things. Fencing is one product that they seem to specialize in, making several different styles, from wattle-type chestnut panels to gates and other picket-style sections fastened with nails. They also make lovely baskets woven with thin strips of chestnut that they produce using a very clever traditional machine - something of a mechanical drawknife. For this, they only use the bottom meter of a pole about 3-4” in diameter. They flatten two faces of the pole and then place it in the jaws of the machine. They only use the bottom 3’ because it is the only section that is knot free - they explained though that they had recently visited a craftsman in western Spain who produces a similar product. There they intensively prune their chestnut stump sprouts so as to eliminate all side branching. While labor intensive, this allows them to use the entire pole which is subsequently knot free. Once the blank is roughed out, the Chevrier’s steam the wood to help dry it out. This helps eliminate shrinkage which would in time cause the woven basket to shrink and form gaps. After all of this prep work, they fire up the machine, and a set of hydraulically operated piston arms repeatedly remove thin slices from the blank, thereby creating thin strips of wood that are invaluable for woven crafts. Because of the fact that the wood is sliced, one side is a bit rough, having not followed the natural orientation of the wood’s fibers. They take this into account when weaving, and orient all of the strips in the same direction. They showed us some small baskets they make with these strips - probably 8” by 4” and 2” deep. Serge and Chantal’s daughter Sandrine who had since joined us told me they charge 6-8 Euros each, though that really doesn’t cover their costs - 10 would make it a lot more economical. Chantal told us they also produce hoops for the wine barrel industry. It wasn’t clear if this product is still in demand or if they’ve moved towards something easier to mechanize (I assume they have). Traditionally, both barrel staves (individually sections used to fabricate wine barrels) and wooden hoops were in high demand in the wine producing regions of France. They would produce these in the woodlands, load them into flat, low boats which they floated off towards wine producing regions downstream where even the boat was dismantled and broken down into usable parts for fuel or other crafts. Apparently, the chestnut was more desirable than metal for the hoop material as it didn’t get broken down by salt on sea voyages. Also the chestnut is resistant to decay so it isn’t decomposed by insects and fungi nearly as quickly. Apparently, different types of wines would feature different numbers of barrel hoops to indicate which variety was contained inside. In some cases, they fabricated barrels as large as 5-10,000 liters (1250-4000 gallons)! to transport wine from France to parts of northern Africa (not all that far away). Much of the region had been colonized by the French, but there were no vineyards, so the wine had to come from somewhere. Another testament to the vital role the wine industry played in driving the economics of woodland management - poles for training grapes in vineyards were a consistent need. To help prevent the spread of fungal disease that was often found on the bark of chestnut, it was actually a law that all bark be removed from the poles to help prevent infection in vineyards. Chantal demonstrated the process of making a barrel hoop. Under the cover of a traditional shelter that woodland workers built, she started with a 8-10’ long, 1.25-1.5” diameter sapling which she proceeded to split in half using a specialized holding device to help her evenly guide the split along the length of the piece. With experience you can create an even, balanced split by varying the pressure applied to the piece - if the split begins to run towards one side, simply apply more force to the thicker half so as to draw it back towards the center. All this was done by bracing the base of the split between a horizontal wooden peg mounted on a tripod. She would hold the sapling tightly just below the split and then press either up or down on the piece to encourage it to continue to run straight. It’s very important that the two halves of the sapling turn out even because even small variations in thickness will make the blank either more or less resistant to bending into a hoop, causing an irregularity in the final shape. Withe 2 even halves, she then clamped the piece in a set of jaws in the very same holding device and strapped on a belt-type device with a small wooden ‘platform’ protruding from one hip that allowed her to support the sapling’s other end. She used a drawknife to to remove the pith from the inner face of the sapling to help reduce the effects of shrinkage and movement, and eliminate this weak first year’s growth. The next step in the process was to place the blank in the jaws of a hand-cranked device that acts to gently crimp the wood, causing it to bend. The tighter the bend, the more frequently you must pass it through the device. Finally the hoop ends are bound together using a thin piece of willow. Another product they shared with us was the construction of chestnut paling fences - well, they didn’t show us the whole process but they did show us how to rive a section of chestnut using a froe into about 8 blanks that could then be bound together using braided wire to form a temporary fence that could be coiled up for storage and later unrolled for use when needed. This is basically just like the type of temporary fencing we see today erected around fairgrounds and sporting events. Here, Serge showed us their take on a riving brake - a stationary tool used to hold a piece of wood being split. Most of the riving brakes I’d see were mounted vertically - 2 uprights with two attached horizontal pieces. One of them is fastened to the uprights horizontally, while the upper one is fastened at a slight angle - say 10-15%. This provides a gap between them of varying size that allows the craftsperson to place a piece of wood between them and use the jaws to hold it while they attempt to control the split. Well, their riving brake was heavy duty and movable so that the splitting action was more vertical than horizontal in orientation. In the midst of these wonderful demonstrations we discussed some of the traditions of coppice management in France. Typically the work was done by farmers during the winter months. They painted an image of a hard, often destitute life, with the farmers essentially living as indentured servants on the chateau estate owned by the wealthy nobility of the land. They worked tirelessly, up to 16 hours a day in summer and basically saw very little for their efforts. Chantal described the life as ‘utterly miserable’. With no hope of owning land, they were forced to erect minimalist pole structures which they covered with a 2’ thick layer of wood shavings to help insulate them and protect them from the rain. In these temporary structures, they lived and worked through the cold, wet winter months. A challenging life that sounded very difficult to romanticize. This struck me as quite a contrast from the traditions I’d become familiar with in the UK. My understanding in England is that coppice workers bid on bits of woodland each year based on the quality of the material it contained and their relative ability to work it up into product. They then moved onto the property, erected temporary structures in which they’d reside and proceeded to cut the trees and convert them into product. Not all that much different in the physical manifestation, but it sounds to me as if the economic structure was absolutely different, with French coppice workers possessing little if any rights whatsoever. We all headed inside to take a look at the work area where they make baskets, toys, birdhouses and more. Chantal brought out several books illustrating their work and some of the traditions of the French countryside. She shared photos of some of the other craft traditions she’d researched and found inspiring and it was absolutely clear that this was far more than a source of income for them - it was a tradition and a lifestyle that they were passionately a part of. In turn, I shared some photos of some of my work to compare and contrast it with theirs. We enjoyed a cup of tea together, sweetened with honey they’d collected from bees feeding on chestnut flowers. It was delicious. In the meantime, Sandrine’s husband, Ian arrived - who coincidentally was from the UK. What a very small world. As the time was ticking away and our daylight fading we set off to look at some of the stands of chestnut that they are managing so we could see their system and the quality of the materials. It was about a ten minute drive to the first site and we passed along a woods road for about 8 minutes on foot through chestnut cants at varying stages of regrowth until we arrived at the first plot - about .5 ha in size (1.3 acres). They had cut through most of this three year old growth already though it was merely a drop in the bucket full of a sea of healthy, vigorous coppiced chestnut stretching far out onto the horizon. This was the best quality coppice I’ve ever seen. The three year old shoots were 15’ plus in height showing a good 8’ of growth in the first season. The stools were remarkably healthy. In fact it was actually difficult to see where the stools actually lay they had been cut so close to the ground. Chantal explained that they actually go so far as to use a leaf blower to clear the detritus from around the base of the stool so that they can make very low cuts. This encourages straight stems with no curved ‘pistol-grip’ form at the bottom which renders the lowest 6-12” or more useless for most crafts. It looked like the stump sprouts were emerging clear from the soil surface. It was difficult to make out the size of these stools and we didn’t find out what their projected age was, but they must’ve been at least 100 years, if not closer to 300 based on their girth. They seemed to be spaced anywhere from 6-8’ from one another though it seemed that they could definitely have sustained a regular 6’ spacing for this size growth. This was a simple coppice system - few if andy standards were visible on the horizon. They’ve been cutting this stand for 6-7 years now and the attention they’ve put into encouraging healthy growth was clearly evident. Their primary problem here has been deer damage. With no permanent residents living within the coppice and too extensive a stand to actually fence them out, they simply have to accept the fact that they’ll sustain some damages each season as a cost of doing business. I asked if they ever do any other work to attempt to improve the stand and they said no - because they rent they have little incentive to do anything like layering or planting out to improve stand density. These high quality cants are producing just fine as it is and so they’re happy with the relationship. We left this site after only about 15-20 minutes so that we could beat the impending dusk and visit another cant nearby. Along the way we wound through vast expanses of chestnut coppice - and made a stop to observe a pile of 6-8 year old poles 20’ long each - the entire stack probably 15’ high and 40’ long. This is how they store the cleaned up and processed polewood - it’s later collected on a flatbed truck with a grab arm and hauled to their site for conversion into value added products. One thing I’ve forgotten to mention is that Sandrine explained that they always sned their poles (remove the side branches) working from the tip to the bottom. This helps prevent them from damaging the surface of the bark as they clean them up and also helps ensure that they remove the entire branch as the downward direction causes the brach stub to pop free from the pole since it’s working in the opposite direction from that of the growth. This is important for many products as they need to remove the side branches completely so the stubs don’t interfere with their ultimately functionality. The second stand we visited was about the same size and age, though it was adjacent to a more mature stand about 4-5” in diameter. It was definitely less than optimally stocked with fairly large gaps in between stools, but this didn’t seem to result in overly open-growth, branchy growth forms. Instead there I saw probably the most healthy chestnut stool I’ve ever seen - close to 4’ in diameter, by my count it hosted 40 quality stems (Chantal and Serge said it would be more likely to be 30 for their needs). It was clear that the species thrived here and so wonderfully inspiring to see how it continues to bear even amidst the erosion of the craft traditions that once sustained the industry. Chantal told us there were once 2500 coppice workers in this area alone - today there are only 15. Much of the existing coppice in the area is still being managed by wood merchants who buy access to the stands at a reduced rate, but they care little for the health of the stand or the quality of the stems. Most of their management and extraction is mechanical and causes significant destruction to the coppice, the ruts from their machinery tires and the careless cutting eroding the stability and health of the coppice for the long term. It was just about dark by this point and while we easily could’ve continued talking for hours, it was time for us to go. We graciously thanked Serge and Chantal and headed back towards home feeling absolutely saturated from a most enlightening day.

4 Comments

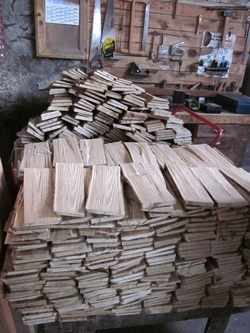

Mark's French Reflection from February 19, 2011 - We’d planned to meet around 10 am Saturday morning and assess the plan for the day. I got up and grabbed a croissant from the bakery up the road. I hadn’t been back long before Michael and Tom arrived with exciting news. His friend Edward had been able to secure a guided visit at a nearby factory that produces chestnut shakes (wooden shingles - bardeau in French). We had been planning to go there Friday but the timing didn’t quite work, so I was eager to learn we’d still be able to make this promising visit work. We drove to Michael’s friend Edward’s house where we picked him up, and he proceeded drove us to our destination. Another British ex-pat, Edward and his wife had moved to France after retirement. Edward was an English teacher at a high school in the Manchester area, is fluent in French and is quite a character to boot. It was only about fifteen minutes by car before we’d arrived at the ‘factory’ and were greeted by the owner Joel Richard (there should be an ‘um-laude’ in there somewhere - it’s pronounced ‘jho-elle’) - a patient, robust man, with a slow, calm way of speaking, a thin mustache and a passion for the work he does. We spent the first half hour or so in the office with Joel giving us an overview of the factory, their products and their process, and us asking questions via Edward to come to a better understanding of the history and background of their business. Joel told us that with the exception of a few companies producing western red cedar shakes in western Canada, they are the only company he knows of that are doing this work by hand in Europe. (and beyond). I initially wasn’t sure if we were going to see shingles produced by sawing or those made by splitting and was now absolutely excited to see their process. (Check out their website at http://www.bardeauxfendus-richard.com/produits_realisations.htm) Joel said that chestnut shakes’ lifespan can vary considerably based on the application and context - the flatter the roof, the shorter they last - but it could be anywhere from 50-100 years. Later in the tour he showed us shakes that had been exposed for 35, 50 and 100 years and it was very enlightening to see how they’d weathered. They charge 55 Euros (about $72 or so) for one square meter’s worth of shakes. They are cut to a consistent length but their width varies a bit. On average, a worker can produce between 250 and 300 shakes in an hour by hand. He has 10 employees and the their retention time is astonishing. The oldest has been there 35 years and the most recent, 15. He said rather comically, people don't leave the business because they want to, they leave because they have to (like, they get fired). When it comes to taking on new blood, if they haven’t gotten the hang of the process in about four hours, he sends them on their way. You can tell if someone will pick it up pretty early on. Joel bought the business in 1956. It had already been active for some time by then. What amazed me most about it was that that meant that he’d been at it for almost 55 years. I would’ve placed him about his mid- to late 60s based on his apparent physical health. To have purchased and taken over a business, he must’ve been at least into his 20s. So he was really much closer to 80. I later learned that the French have one of the longest lifespans in the world (if you don’t account for the young folks killed in driving accidents) - their mandatory 35 hour work week and philosophy on the work’s role in life likely helps support it. They source the wood they use for their products from about a 12 mile radius. They typically buy the rights to the standing timber on a property - just like things were done in many of these countries traditionally. There’s no problem finding quality wood - it’s abundant in the area. In addition to their ten employees they retain 2 teams of two who do their cutting and raw material procurement. Joel said the ideal log is about 6” in diameter. Larger diameter wood often is more prone to wind damage (or wind shake - a delamination along the growth rings of the tree caused by excessive exposure to wind). He also said that as chestnut matures it tends to warp and twist more. About 70% of the total wood they cut for shakes is too poor quality to use for shakes. Fortunately, there’s no waste, as they also deal firewood and kindling. Thus, their by-products are still a useful value-added product. The shakes are installed while still green. As many of you likely know, wood shrinks differentially in each of it’s three planes. Longitudinally, the shrinkage is negligible - like 0.1% so that really makes no different. But depending on the species, wood will shrink between 3-6% along its radial plane and 8-10% or so across the plane of the growth rings. While this knowledge is valuable, it really doesn’t matter for the shake installer because of the simple fact that wood is ‘hygroscopic’ - it fluctuates in its moisture content with changes in relative humidity. When the air is dry, the moisture content in the wood reaches an equilibrium with its surroundings and it dried accordingly and the reverse is true as well. If they were to only install dried shakes, when the air is humid, the shakes would swell. If they’d butted each shake against one another edge-to-edge, they would buckle. So instead, they stall the shakes green, butting each one up to the next, fully knowing that they’ll shrink over time. The considerable overlap between each row (only about 1/3 of the length of each shake is exposed to the elements) means no water can penetrate the roof. Once the shakes fully shrink and dry, the result is a small gap between each shake that is perfectly sized to accommodate for subsequent swelling during times of high humidity. What a great system! Around this point in the conversation, Joel agreed to bring us into the workshop and show us the operation. With pallets of shingles stacked all around, their scale of their production was clear. In total, they produce 10-12,000 square meters of shakes each year - limited more by demand than their ability to produce them. In addition to roofs for houses, barns and other structures, much of their business comes from organizations devoted to historic preservation, replacing old and worn shakes with new ones. I never found out whether or not they also install their product, but I was led to believe that they simply ‘manufacture’ them. It’s challenging producing a product that has such a long lifespan - in some ways you design yourself out of a job. To stay competitive, they’re also considering marketing their sawn shingles more actively (they do currently produce some), as the bottom line better supports the business economically. That said, they’re not really in it for the money - if they were, they’d be doing something else. They love their work, and it absolutely showed. On the exterior face of the warehouse/workshop, a painting illustrated the vital role chestnut plays in this process. A lone chestnut gives way to a tree which is then coppiced. The next panel features stump sprouts emerging from the cut stool that later grow back into poles. This simple pictograph clearly portrays the elegant cycle. Inside the shop various machines and devices proved a feast for the value-added, craftsperson’s eyes. The first thing I recognized was the impressive shaving horse-like holding-device design. Edward translated it into a ‘goat’ - I’m not sure that that’s technically what they call it. The device is used while standing, rather than sitting as one would do while using a shaving horse. The clamping mechanism features a fabricated steel arm and leg which are tensioned via the action of a heavy spring that keeps the jaws in the open position when not engaged. The wooden base includes several short steel spikes embedded into the surface to help improve the grip. This is a well-engineered tool, perfectly suited to their needs. They also have machinery that can be used to mechanize the process including a mechanical splitter, but Joel demonstrated the traditional process for us. He told us that it would be difficult for machinery to perform any faster than a skilled worker could by hand. Effective work requires a keen eye and an attention to the details of an irregular material that would be difficult to automate. Thus, skilled labor is still a highly valued asset that fortunately can be sustained by the current market value for their products. Joel started off by grabbing a bolt (section of chestnut log) that looked to be high quality. He then picked up a ‘de pert tois’ - or what we would call a ‘froe’ in English. Essentially a long thin wedge with a handle affixed at a right angle. The tool is used for splitting, or riving (or cleaving in the UK) wood in a controlled way. Joel began to systematically reduce the chestnut round into probably about 8 rough split parts. These rough parts really weren’t all that rough - they only required a few seconds of hand work before they were ready. Riven shingles (again ‘shakes’) last longer than their sawn counterparts under most conditions for a few reasons. Firstly, the fibers of the wood haven’t been severed by a saw blade so the cellular structure of the wood isn’t nearly as exposed to water, fungi and other decay organisms. Also, the grain of the wood is running clear through the piece which makes them stronger. And finally, the rough surface of the shakes that comes as a result of the splitting process physically acts like a natural landscape complete with ridges and valleys, channelizing water and directing it away and down the shake more actively. After riving the shakes, he then used a violent-looking relative of the froe, with a curved blade, a razor-sharp edge and a set of teeth carved into the short end of the tool. Joel used it to remove the sapwood from each blank with a hewing motion as one would do with an ax. This was a tool I’d never seen before, and being the traditional craft junkie that I am, I was nearly drooling over it’s clever design and functionality. On the wall, I noticed a gorgeous single bevel (hewing) hatchet with a bulbous handle. It almost looked like something out of a cartoon - I had to ask what it was for. Joelle explained that it is actually used for the same purpose - to hew off the bark and sapwood from the split shakes. He passed it around and told us that the swollen handle base is a clever way of helping balance the tool in use - it acts as a counterweight against the heft of the handle - you could definitely feel it work in your hand. The next step in the process was to taper the shakes so the top end was narrower than the bottom and they would fit onto the roof surface more evenly. As I mentioned earlier, only about 1/3 of the length of each shake actually remains exposed on the roof, so the smooth shaved surface of the shake isn’t exposed directly to the weather. This was a quick process carried out on the ‘goat’ with a razor sharp drawknife. Many of these tools are difficult to come by today. Or if they are available, they are either of inferior quality or expensive to obtain. It was clear that many of their tools had seen considerable use over time, picked up over the course of several decades. While on the goat, Joelle showed us how quickly and easily he could add a chamfer to the bottom edge of a shake, conferring an aesthetic detail to the product. This only adds a small cost to the product at the end of it all. For plain retangular shakes, the process would then be complete. But they do offer more decorative patterns - including rounded and pointed bottoms. To do this, they use a tool whose name escapes me, but it’s one I’d only ever seen before in books. I had associated it with clog makers in northern Europe after having seen it illustrated in John Seymour’s beautiful book - The Forgotten Crafts. The tool features a heavy log base supported by 3 or 4 legs. Three legs are actually easier than four to keep level on uneven surfaces. A heavy, stationary metal ring is affixed to the log base near one edge and then a tool that looks like a heavy-duty machete with a hook at the tip is engaged with the ring so as to lock the tool in place. This essentially fixes one end of the tool and provides the user with considerable leverage to do their shaping work. It also allows them to pivot and control their work remarkably effectively. The use of this tool in action is beautiful to watch. Efficient, graceful and ergonomic, Joel was able to add aesthetic details to each shake in a matter of only a few short seconds. And with that, we’d seen it. A low-tech, highly skilled approach to adding value to a wonderfully, rot-resistant polewood species. After our demonstration was complete, Joel showed us a few more illustrations of some of their work installed, and we chatted a bit more about the process and the economics of their business. They’re staying afloat but they’re definitely not growing was the most concise way to put it. This wonderful man left me feeling inspired by his passion and dedication to this craft and excited to locate or fabricate some of these new tools once I return home. We left the factory feeling almost giddy with excitement - and this was only our first of two stops that day. Edward took us on a short detour through a nearby town on the way home to visit the basilica which featured a roof fashioned from Joel’s shingles. We took a few minutes to explore the interior of this holy house - more than 5 centuries old with it’s massive granite columns and impressive upper dome. We then west to the edge of the village - which lay along an important pilgrimage route that’s existed for hundreds of years, and enjoyed the sweeping views of the surrounding countryside. From there, Edward dropped us back off at our car, we raced home for a quick lunch and then set off towards the south - about an hour’s drive to visit the Chevrier family who have created their business around the management and value-adding to sweet chestnut coppice…. Here's Mark's next installment ... I awoke on Friday morning in a comfortable, unfamiliar bed. My British, turned-French host Brandon called up to me to let me know coffee was ready. He sure knew how to get me up. I headed downstairs and found him at the kitchen table. We sat and talked for an hour or so, Brandon filling me in about his experiences connecting with the locals in the village as we saw several of them pass by, enjoying a quite morning in the hills. He told me about one elderly man who would head out to the fields each day to cut grass with his scythe to bring back to his animals. As we were chatting another man who must’ve been in his 80s headed out towards one of his fields with 2 chestnut fenceposts in hand to place somewhere around the perimeter of his field. This reminds me of an important property-ownership point I’ve yet to make. Early on in my conversation with Michael, I learned that property ownership in France grew exceedingly complex as a result of a decree by none other than Napoleon back in the day. This legislation required that property be split evenly amongst each descendant so that what was once a relatively large inheritance and contiguous property has now become a network of disconnected fragments with little relation to the whole of which they were once a part. Thus the 10 or more (I can’t recall how much specifically) hectares (2.6 acres to a hectare) that Michael owns are spread out over a vast, disconnected land base that features a range of shapes and sizes. The whole thing is so complicated that in many cases, people aren’t even aware of parcels they might own and so they lie as derelict fragments within a severed whole... As we finished our wholesome porridge breakfast, Michael and Tom arrived for our first outing of the day. The previous night Brandon told us about ‘le gran chene’ - the big oak. It’s a massive ancient oak tree that was only a 10 minute or so drive from Bossabut. Being the tree lovers we are, we set off to check it out. On the way, I had a chance to see some of the architecture of Brandon’s village that was hard to make out the night before. The barn on his property features some amazing old timber frame joinery with some impressive rough hewn beams, and we passed another building in the village with stunning vaulted stone basements (exposed on the downhill side). A few miles away, we pulled off the road and took to a well traveled footpath through the countryside. Within about ten minutes, we came onto what appeared to be some traditional form of water distribution canal, complete with sluice gate. It was difficult to tell exactly what it did but my mind quickly took off imaging a keyline-type food flow irrigation that ensued as the sluice gate closed and the water backed up in the shallow, near contour tench behind. It was undoubtedly some type of human created earthwork used for moving water passively through the landscape - a relic of a land use tradition now nearly forgotten. We crossed a lovely wooded stream and just around the bend came upon a most stunning site - an oak tree that boasted a canopy that easily spread 70’ in width. The landscaping around this massive tree bore the reverence of peoples over several generations, with a deteriorating wooden fenceline around the perimeter and a grassy understory devoid of woody vegetation. We spent a good fifteen minutes admiring this marvel of nature and relishing the experience to convene with such an ancient creature. To date, this journey has already proven to be a stunningly deep invitation to recognize the intimate depths of humans’ relationship with trees and landscape. Le gran chene was yet another moving installation in this passage. Brandon needed to return home for work, so we paid our respects and returned to the village. From there, Michael drove us back to their home, from which the two of us proceeded to explore his property so that he might show me the work he’s been doing to restore health to a recently forgotten landscape. First he showed me maps of the parcels he owns and how painfully disconnected so many of them are. Much of Michael’s landholdings feature remnants of chestnut coppice woodland. That’s the sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa). Like the UK, the Romans brought it with them as they expanded and colonized much of Europe 2000 years ago - yet another testament to the incredible utility of this amazing species. At this point, much of the woodland is suffering from a severe lack of management over the past generation and beyond. The woods are choked with growth and the chestnut stools that have survived have far too many stems to support given the interval since they were last cut. Michael’s management goals focus on restoring health to this forgotten woodland. He’s not personally interested in producing small diameter polewood for crafts nor has he cultivated a market for these types of items. Instead, he’s looking to continue to build on his fuelwood sales while increasing the potential to extract quality timber which he can mill up on the bandsaw mill he’s setting up outside his barn. While this isn’t necessarily within the purview of coppice establishment as we’re seeking to explore in our book, it certainly bears relevance as it’s another take on woodland management - effectively stand-scale pruning for community health. And given the fact that Michael has inherited this ‘overstood’ (neglected) coppice at the outset, it’s immensely illuminating to examine how one goes about shifting the structure of this polewood-based tradition towards something that looks more like a ‘high forest’ in form. We looked at some old pollards that were long since cut, chestnut stools that still bore a physical resemblance to what they must’ve looked like decades ago and the legacy of snowloads and windthrow on trees spread too broad for the root systems that support them. Michael steadily works to actively thin the woods so as to favor the trees with the most potential and the best form with the hopes that they’ll develop into high quality saw logs over time and encourage a more balanced stand structure. Many of the chestnut stools in these stands are massive and require much more careful attempts at restoration than simply cutting them to the ground. As we saw with the management strategies at Burnham Beeches, the restoration of derelict coppice is in many ways a new and emerging discipline that requires practitioners to learn as they go and actively experiment. After having lost a large chestnut stool as a result of attempt re-coppicing gone wrong, Michael has become a bit apprehensive about his strategy. It was difficult to tell why it was that that large chestnut stool didn’t resprout from his coppice attempt. In my mind, limited light seemed as if it may have played a big factor as it appeared to be well wooded to the south. Michael didn’t agree though. He was left feeling a bit uncertain as to how best to approach the restoration of these over-mature stools. Another possibility leading to the demise of this stool could be it’s relative maturity when cut. Many trees lose their ability to resprout with age. Perhaps as is done with pollard restoration work, it would in this case be best to approach the cutting incrementally - leaving an existing stem in place so the tree may continue to photosynthesize - in pollard restoration, they call this a ‘sap riser’. We made our way back down to the house for lunch and tea (Michael is British of course!) and an hour or so later set out to look at some of the stands he was particularly satisfied with after having been working to restore their health for several years now. Here we saw a much more appropriately spaced structure with many of the overstood stools now featuring only one or two stems. Again, the plan is to approach these cuts slowly and steadily - sort of a ‘measure twice, cut once’ approach - applied over the course of decades. After clearing the woods of the thick scrubby growth that had been choking out its potential productivity, Michael will return in another couple of years to thin once again - at this point, it should become even more clear as to which stems should best be removed and converted into fuelwood and which ones have the most promise as sawlogs in another decade or two. He told me about the challenges in thinning around coppice stools and standard trees that have been previously supported and protected by the trees that surrounded them. One must be careful when approaching a thinning to make sure they don’t remove too much of this shelterwood lest the stools and standards suffer the effects of high winds and topple over. A little further along, we saw the effects of this with considerable swaths of woodlands downed as the result of windthrow. While conversion of coppice stands via thinning towards more of a high forest structure wasn’t necessarily something I’d originally sought to observe, it was fascinating to see how the legacy of neglect translated into a variant of this type of silvicultural management. I learned a lot from Michael and the set of eyes he brings to the woods - and as it should, it all comes back to his goals and what he perceives to be the needs of the land. Without access to a market for polewood and an interest in developing the livelihoods associated with value added crafts in this way, this management approach was absolutely appropriate for the context. That evening I spent the night in a hotel in a nearby town, catching up on communications from the past few days on the road. Resuming where I (Mark) left off last Thursday, February 17 -

(note, if you don't want to read a story about getting from A to B, then maybe wait until the next update from me (Mark) - this is all about getting there and the people along the way - thanks!) I took the train from the village of Haselmere into the city of London with one change along the way. The verdant rolling countryside along the way speaks little to the utter density of development in England. With a population of 51,446,000 in 2001 settled on a landmass 51,346 square miles, the math is fairly simple - about 1,002 people per square mile. Compare that to the state of Massachusetts with 6,547,629 people according to the 2010 census spread across 10,555 square miles - about 620 people per square mile. (Note - strangely wikipedia states that MA’s population density is 809.8/sq mi - the third most densely populated state in the US (after New Jersey and Rhode Island) - I double checked my math using the same figures I got from their site and came up with 620 yet again. Who knows?) The point is - there’s a lot of people in the British Isles. But despite the density you still get a feeling of open, working agricultural landscapes while traversing the countryside. (Of course, this density comes at the expense of ‘wilderness’ - or otherwise undeveloped land.) And really all that just to say that it was a lovely train ride to the city of London. Once there, I hopped on the tube to cross town where I was to catch my Limoges, France-bound train at the London St. Pancras station. While this is kind of an aside, I feel it bears worth mentioning. Right now, I’m in Madrid (Spain) and popped out to pick up a bottle of wine to help inspire the reflective process. Apparently they stop selling alcohol at 10 and I arrived at the first shop at 10:05. The man behind the counter proceeded to nervously take me towards the back of the shop where he proceeded to remove a display rack holding some type of shrink wrapped pastries probably ‘baked’ 3 months ago, behind which stood a set of cupboard doors. He opened the doors and hurriedly told me to pick out what I wanted from the extensive selection of wines hidden within the storage space. I picked out something (didn’t really feel like I had time to be choosy) and he then proceeded to quickly bag it for me, take my money and usher me out. How’s that for some adventure? Wow, does life ever seem exciting these days. Ok, so that’s just a bit of context. Now back to the recount. I had some time to kill before the train departed and spent it in a pretty schmancy (that’s definitely not a word - at least the way I spelled it) little cafe, catching up with some e-mails and making sure my last minute plans to meet with Michael Ashby in Limoges were all set. With 15 minutes before departure, I rushed towards the platform where I learned that I was actually subject to an international airport-like screening process complete with x-rays (thankfully they didn’t take my trusty Opinel knife - I can’t believe they didn’t actually), metal detector, passport check… I was getting nervous I was going to miss it - or get deported, but I made it and boarded a sleek, new European train bound for Paris. Struggling to keep awake from days of full-on living and a comfortable window seat, I found myself retreating in and out of dreamland which meant I completely missed our passage through the channel tunnel. I regained some consciousness wondering if we were still in the UK and found the nearest commercial development sign that clearly indicated we had entered French territory. The landscape was about as flat as flat can be (though I don’t actually believe that any landscape can actually be ‘flat’, as it all - well almost all of it - has to drain somewhere). Peppered with a smattering of industrial buildings interspersed between sprawling farmland (most of it in some type of cover crop or hayfields), the landscape was relatively benign until we started to see some changes in topography and a bit of forested land. Within another hour we began to enter the Paris metropolitan area, and open space gave way to urban development. We arrived at the Paris Nord train station where it was time to change trains. Like many major European railway stations, the facility boasted remarkably high glassed rooftop, feeling about as open air as an airplane hangar-sized structure possibly could. Switching currencies, languages (one for which I’ve got about a 30 word vocabulary) public transport systems, and stations all in one go over a 1 hour layover was a bit much. Fortunately, the Paris Metro is very self-explanatory and I had Euros leftover from my last trip to Europe nearly a year ago. I had to head across town to the Paris Austerlitz station. It all was pretty straightforward, the only downside being that I was in Paris but had zero time to actually say hi to the cityscape. The Austerlitz station wasn’t nearly as bustling as that of Paris Nord but I guess it really didn’t matter as we were off within 45 minutes. I grabbed a ‘pan au chocolat’ before boarding and enjoyed a pretty low key journey south. We started to see more woodland emerge as we escaped the bustle of the city with the tracks frequently lined by healthy, but unmanaged hazel stools and oak-dominated forests. It was pretty dark by the time we reached the station at La Souterraine - about 30 minutes north of Limoges - where my English-born, French-residing host Michael had agreed to pick me up. Just as I left the station, I made eye contact with a tall, full-bodied, kind-looking man rapidly approaching. It seemed that we both ‘recognized’ one another at the same time, and despite the fact that both of us were ‘late’, our timing was impeccable. We said hello and headed for the sweet 4wd 90s?, driver on the right side, Toyota minivan that was to be our ‘tour’ bus for the next couple of days. I scarcely had a chance to absorb my new surroundings before we were headed back towards Michael’s family’s home about thirty minutes away. What I can say though was that the buildings appeared as one might expect in a traditional French town - well proportioned, solid, and oh-so-aesthetically pleasing configurations of local stone and tile rooftops. The moon must’ve been full as we passed through the rolling countryside for we could make out much of the detail on either side of us as we got to know one another a bit beyond the limited e-mail exchanges we’d had during the lead up to my visit. I discovered Michael via a google search for something like ‘coppice France’. Michael is an avid woodsman - an absolute lover of trees and all of their products and potential. He nurtures a fantastic blog as a mechanism to share his insights and musings with whomever in the world cares to read it - http://myfrenchforest.blogspot.com/ As a start up nursery man in his early professional years, his life has taken several turns along the way, the most recent of which (13 years ago) led him and his family to relocate to the countryside north of the French city of Limoges in what I was soon to learn is located in the exquisitely beautiful Limosin region. Looking for a place where they could afford a house and some land, they stumbled upon a property that suited them perfectly with a mortgage that would cost them less than what they’d been paying for rent in the UK. And that was it - they relocated and the rest is history. So as you might guess, I’m glazing over a whole bunch of details, but that more or less brings us to the present which is likely why you’re taking time to read this in the first place. After extracting some cash from an ATM and a half hour on the road, we arrived at the Ashby chateau, where I was greeted by three of his four children (Andrew, Oliver, Tom - Tim would return the following day) and his wife Angela. On the way back, I learned it was Andrew 17th birthday and so Michael got to preparing Andrew’s requested birthday meal - fish cakes and chips. Their home is a cute, sprawling, old stone French building (or series of add-ons) with hand-hewn chestnut roof timbers, low ceilings and a lot of character. I sat around the table with Andrew and Oliver, who I believe had not yet met an American so we set to task, getting clear on what the Land o’ the Free is really all about. It was a kinda like a fun interrogation by some eager interviewers - but I was ever so aware of the fact that I was to date, the sole real American diplomat to shape their views and do my best to undo the stereotypes of American life. It really is amazing to learn what people think we’re like in real life, people (I guess ‘people’ here means the American readers.) Well, fortunately for those of us that tend not to follow the status quo, I’m not you’re ‘typical’ American so I probably shattered some typical assumptions, namely - I’m fairly slender, I don’t watch television, I don’t have an SUV and I don’t eat McDonald’s. After Michael ‘grilled’ our dinner and the kids (lovingly) ‘grilled’ me, we ate Andrew’s birthday dinner, followed up by a decadent chocolate cake. I definitely picked the right night to arrive. We continued to converse until about 11 or so, when Michael, his 3/4ish year old son Tom, and I headed to Michael’s friend Brandon’s house in a nearby village where I was to stay for the night. We passed by some chestnut coppice along the way - the first active signs I’d seen since my arrival in France 8 or so hours earlier - and climbed up to the village of Bossabut (I think was the name). Brandon’s lovely home was located at the top of the village where I was assured I’d enjoy incredible views come morning. The three of us met Brandon on his landing and made our way into his restored stone maison where he offered us beers and I gladly obliged. We sat around conversing for a bit and sharing stories until Michael and Tom set off for home. Brandon showed me around the house - I was astonished with his kindness and willingness to share his place with a stranger. Originally from northern England, he’d travelled quite a bit in life and had spent time as a DJ working in New York and LA. Somewhere along the way he’d found this village in France and knew it was the place for him. He’s since become a builder and handyman for folks in the area, growing familiar with most all of the tasks necessary to renovate and retrofit these centuries-old buildings. He has a keen appreciation for the quality of life that the people in the villages enjoy and the way they’ve preserved so many of their traditions. It was humbling to hear how open they were to newcomers who demonstrated a commitment to the village and how much he admired their spirit. We stepped outside for a bit to enjoy the cool night air and the magnificent moon. Up above the house, we sat out on a bench he’d built overlooking the fields below. It was amazing to imagine the possibility of picking up shop and moving to such an idyllic location. It seems well within reach both economically and socially for anyone interested in doing it - well, except for the economic part - meaning that it’s economical to buy there but earning a living may prove to be a bit more of a challenge. Either way, it was wonderful to have met several folks already who had chosen to do just that. Feeling a bit worn from a full day (is it really still the same day?), I checked in for the night, eager to see what the rest of my time in this magical land would bring. For those of you looking for details on coppice, read the next installment (sorry to tell you this at the very end). This was all just to set the scene and develop the characters a bit. Good night! After leaving Longwood Gardens, I headed south into ice-free roads, but still a snow-covered landscape. The next morning I realized I had a damaged tire from that deep NJ pothole, and gave into a few hours of waiting while spending $400 to get what I later realized was a doubtful pair of new tires and a questionable alignment. Nonetheless, it was better than a blowout, so I headed into the "wilds" of Maryland to find Leon Carrier and his humble homestead. I found Leon in his greenhouse out behind the small, typically suburban house with an atypical yard full of mulch piles, a 20 x 20 greenhouse, a delivery van, and various and sundry items needed to run a small nursery-type operation--not to mention the rows of woody perennials lined up and packed into various areas of his own and his neighbors' properties. While Leon and Carol own only about 2 acres, they have five under cultivation: neighbors let them use their lots, and they grow winterberries in the ditches along town roads! Leon and Carol don't have to pay taxes on all that land, the neighbors get to mow less, and Leon and Carol give them a few flowers during the year. Such a deal! Leon's unassuming manner belies his confident, grounded, matter-of-fact nature. Even though he admits to making it up as he goes along, he has found his niche, he knows it well, and he makes a decent living for one who works the land. Leon is one of the few, the proud, the cut flower growers. Such folk appear few and far between, and their production is dwarfed by global corporate industrial systems, but Leon was the first of several I met on this trip that have worked out how to dance around the dinosaur's feet and have fun doing it. The fact that he lives 30 miles from Washington, DC helps make that possible: Gaithersburg lies in one of the USA's richest counties, a place where people feel unafraid to pay for flowers, and don't seem to know much about what they buy besides the fact that they like their look. Leon is happy to cut from crabapples and dogwoods that the previous owners planted--he'll cut from anything that sells to make his living. But he also works hard, or plays hard: he loves working in the dirt and working with plants, despite the long hours. Leon and his wife Carol began growing flowers 22 year ago on this property. Mostly clay soils and former cow pasture, the soil is pretty good and they've made it better over the years with lots of organic matter additions. Leon loves his mulch--he adds copious amounts (up to 5 inches of wood chips per year) to control weeds and limit drought, as well as to add nutrients to his land and crops. The woodies in particular don't need much besides that--perhaps a light top dressing of nitrogen on some species. The woodies also take much less work than his few herbaceous perennial flowers--no digging, dividing, less weeding and fertilizing. You harvest and harvest, and cut them back hard every year or every three to five years, and you mulch, and that's about it. A few weed patrols for pokeweed, bindweed, and some unknown grape-like vine, but that is about it. They grow lots of different Hydrangeas, lilacs, pussy willows, winterberries (10 different varieties), dogwoods, viburnums, rose hips, Symphoricarpos, snowberries, plum, cherry, crabapples, flowering quince, magnolias, forsythia, and more. Some of these they harvest for their flowers, some for their ornamental berries, some as backing greens for arrangements. Some of these Leon took from cuttings from cut flowers he bought from others, or from plants he saw that he liked in various places. They sell mainly to farmer's markets, but also some to florists in the area. They make a solid and decent income, but don't live high off the hog. And it can't be cheap to live in Montgomery County, Maryland, either!  Leon with a row of Hydrangeas and two rows of Ilex verticillata (winterberries). The Hydrangeas (first row from left) have been cut back hard during the dormant season to allow new sprouts for flower stem cutting in the coming year. The snowy blank space behind the Hydrangeas contains Ilex that have been cut to the ground for coppice regrowth this year, but will not flower and make berries til the end of the second growing season. The shrubby row of Ilex behind were planted 13 years ago, and he's been harvesting form them ever since. He's now converting that system to a coppice system with a minimum three-year rotation.  One of the many Hydrangea cultivars, close up, showing the "technique" of cutting back after the harvest season. Leon uses a power hedge trimmer, and just "gives them a haircut". This is not "horticulture" per se. Attention is not paid to careful pruning for the best health of plants (clearly!). But it seems to work, and has for many years. There may be room for improvement in technique--but this is certainly an expedient approach for a small-time operator with limited labor and time.  This flowering quince shrub currently has 60-80 bunches of stems on it that are harvestable come the growing season, and that Leon can sell for $10 per bunch: $600-$800 per shrub. That kind of $ yield is VERY hard to beat with any other product. AND this species suckers and spreads on its own. Too bad it isn't the quince that gives quality edible fruit, too!  These two rows of Ilex show the transformation to a coppice rotation they are currently undertaking. The row in back are again abotu 13 years old, and have been harvested many times without cutting back to the ground. They were planted at a 6-foot spacing, but sucker to fill in the row. The row in front used to be like the one in back, but was cut to the ground last winter, and have one year's regrowth on them. These stems will flower and make berries this coming year. Leon hopes each single stem seen there will branch multiple times to make a nice sprig with numerous berries on them for fall harvest. Five multiple-branching stems in one bunch can sell in his area for $15--$3 per stem. That front bed is about six feet wide by fifty feet long, and easily contains hundreds of single stems. It is only one of many beds of Ilex Leon and Carol have.  This plant is called Magnolia grandiflora 'D. D. Blanchard'. It's dark brown underside is its main selling point, along with its size, texture, and long-lasting color. The bunch in Leon's hand would sell for about $6. He estimates that the tree behind him yielded about 125 bunches last year--and will yield the same in the coming year and every year thereafter. It just keeps regrowing. He has five of these trees. Is this coppicing, pollarding, shredding, or a combo, or none of the above? Does it matter? It works, that's what matters. I returned late last Friday night from a 19-day, 10 state, 2,600 mile journey with 8 teaching gigs, one radio interview, and 6 coppice research visits--and requiring two new tires and an alignment from hitting a serious pothole at high speed on I-95 in New Jersey. I'm rejuvenated after spending most of Sunday sleeping, so I'm finally reporting to "y'all" from my trip to the southlands. I'll start at the very beginning, it's a very good place to start . . . I left early for the trip to avoid the Feb 1 snowpocalypse and to make sure I met my scheduled coppice visits at the beginning of my itinerary. I headed first to Kennett Square, PA for a slippery tour of Longwood Gardens on forbidden, icy paths. I had heard through the grapevine that this former estate of Pierre DuPont had some coppicing and pollarding going on. Email contacts had lowered my expectations of what I would find, but Rodney Eason of the Longwood staff was more than willing to take me on a tour despite most of the place being closed from the storm, so I agreed. Rodney and I met along one of the main paths to the Conservatory at Longwood. He told me that back in 2001 or so, they had planted an allee of Paulownia tomentosa trees (princess tree) along this path. However, the trees grew crooked and misshapen, so they cut them all to the ground, allowed them to coppice, and thinned each to one stem. Now, 8 or 9 years after coppicing, the trees are all at least 30-35 feet tall and 12 inches in diameter! Granted, they get pretty much the best possible care and feeding a plant can get (Longwood reportedly has a $40 million annual budget), but still, Paulownia is known for its rapid growth, and these trees are certainly evidence of that. While Longwood grows them for ornamental use, Paulownia wood has a multitude of practical uses, including for boxes, crates, and palettes, charcoal, furniture, cabinetry and woodworking, joinery, gunpowder, musical instruments, and shoe or clog soles. The species has long been touted as one of those savior plants in tabloid gardening rags--earning my skepticism and scorn--and raising other people's ire as a potential "invasive." The growth rate is awe-inspiring, though, and leaves one pondering the possibilities, as well as the potential problems. This species certainly deserves further research and consideration, which Mark and I will definitely give it! Two of the other examples Rodney and I slipped and slid our way to see were again allees--one of Norway maples (Acer platanoides) around a European-style courtyard, and one of littleleaf lindens (Tilia cordata) encircling an Italian water garden. Both of these were intended to create tall "green walls" of vegetation to enhance the drama of visual experience. By heavily pruning the trees at upwards of 30 feet high, they created a flat-topped, vertical-sided hedge of what were essentially pollarded trees, sometimes complete with developing "clubs" of callous tissue from which new adventitious buds grew. Looking more closely at some of the cut branches, I wondered at the biophysical impact the ongoing pruning was having on these trees, with long stubs left on branches providing openings for pests and diseases. But given the scale of the job and the resulting time crunch involved, it is hard to imagine more care being taken to prune in a way that would harm the trees less. This became a theme throughout my mid-Atlantic journey, as we will see. Rodney also showed me some Arctic blue willows against one wall of the Conservatory building that get cut every year and regrow from the stumps to reveal beautiful bluish foliage and stems. A stunning display in the growing season, they did not look like much in winter, under snow and gray skies. After tense-legged wanderings on the frozen water covering Longwood's pathways, it was a relief to ease my bodymind meandering on walks with plenty of useful friction underfoot through the FOUR-ACRES (!) of covered Conservatory gardens in 19th century style and tropical warmth and humidity with orchids flowering, a piano playing in the library, coppiced forsythia blooming, waterfalls rumbling, and the continent's largest green wall--nourishment for the eyes and the winter-time soul. While not the most useful visit for coppicing research, it was still a good place to see, and my conversation with Rodney may have nudged this eminent gardening institution into some new directions. Only time will tell! Here's the next installment in Mark's European travels...

After a few train changes in Redding and Guildford, I arrived at the station in Haselmere and not long thereafter Ben Law pulled up to collect me. In the midst of his usual hectic schedule, he'd thankfully made time to get me, saving me what would've been a damp and dark 3-4 mile walk to his home in Lodsworth. We wound through the narrow country lanes and were at his house in the woods within twenty minutes. We spent the evening catching up about our respective projects and lives. For those who aren't familiar with him, Ben Law is as close to a forestry superstar as one may expect to come. Having now published four books and been virtually immortalized by the British television show 'Grand Designs' which documented the start to finish construction of his roundwood timber frame, volunteer-built, straw bale house, he's helped to repopularize traditional woodland management and crafts amongst an audience that had likely been more or less oblivious. Living in west Sussex on 8 acres of chestnut coppice (and managing about 100) in West Sussex - about an hour southwest of London - Ben has created an impressive homestead and thriving business int he middle of the woods. I spent 8 months apprenticing with him during the winter of 2002-3 and the experience was one that changed my life forever. Between managing nearly 100 acres of woods, marketing value-added wood products, mentoring two hard working apprentices, fatherhood and maintaining a growing roundwood timber frame construction business it's hard to imagine where Ben finds time for just about anything. That said, he always makes time for quality meals and we enjoyed a dinner of local steak and garden grown potatoes and greens with his teenage son Rowan. After the meal, we watched Ben's most recent TV appearance - a segment on NBC's (USA) Nightline news magazine program. This short piece explored the British plight to control the rampant gray squirrel population in the UK, introduced from the States well over a century ago. The grey squirrel is one of Ben's most pernicious pests in the coppice, peeling the bark off young living coppice poles and eating the cambium beneath. While this typically doesn't kill the pole, it damages the wood and renders it virtually useless for most of his products. The Nightline segment explored the efforts to control the pest which has been displacing the native red squirrel, featuring a patriotic speech by Prince Charles, a fine restaurant with gray squirrel on the menu and finally, Ben and his well trained 'lurcher' (dog) Oily, taking an NBC newsman into the woods, armed with air rifles, with the goal of bringing down a shared meal. Ben has trained Oily to locate squirrels and chase them up a tree, then keeping a close eye on them in the canopy until Ben can follow up and bring them down. It's quite a sight to behold. And of course, they don't waste the animal upon death, instead squirrel has become a common meat source for Ben and his apprentices throughout the year. It's actually a fine meat, not unlike rabbit in texture - alas, they really only amount to a single serving. Nevertheless, it's a great example of how we might turn a management problem into an active yield. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Wednesday morning we set off for their current timber frame building project about 40 minutes away. Located at a family farm seeking to expand their operation to offer accommodation to visitors and guests, the substantial structure was probably about 25'x60' or so in size. Ben explained that they've really honed their process since first building his house over eight years ago. Now with a trained crew of 4-6 builders, they just about maintain a steady year-round building program and have built a reputation for completing their projects on time and under budget - a feat for just about any building company. With a strong emphasis on local, natural materials, they attempt to source their timbers on-site or within the local community. They also source siding (typically oak) and shingling (this time western red cedar) in the surrounding area and have them locally milled. Often at least some part of the building's walls are built using highly insulative straw bales and when we arrived the crew was about to resume work after a lunch break, applying the finish coat of lime onto the interior bale walls. These roundwood building techniques have now become almost formulaic, utilizing a framing style known as a 'cruck frame'. The cruck frame is essentially an A-frame built using heavy timbers and is believed to be one of the earliest forms of building construction in the UK. Because the triangular form of the A-frame is held rigidly in place, two or more of these heavy wooden frames can support the ridgepole and thus perform all of the structural functions the building requires. Often historically, builders sought out curved timbers to form the crucks, sawing them in two so they were 'bookmatched'. This created a more organic shape and higher edges along the walls, providing more head room for occupants. Timber frames later evolved to include jowl posts that create vertical wall surfaces so as not to compromise functional space within the structure as one might expect from an A-shaped frame. For those interested in the subject, two of Ben's books - The Woodland House and the recently released Roundwood Timber Framing both explore the building process and techniques. Also, if you do a search for 'Ben Law Grand Designs' you should come upon the 50 minute television program that documents the construction of his home. While catching up with the builders and examining the buildings progress, I took a few minutes to call Rebecca Oaks, a coppice worker in central England who recently co-authored a book of coppice management and craft. Our time limited by my phone's expiring pre-paid minutes, Rebecca explained her experience with coppice in her area. Working largely with hazel and ash, a good part of her work has been focused on the recognized conservation benefits of coppice. Organizations like Natural England and the National Trust actually provide funding for folks to cut coppice stands so as to create habitat for wildlife, some of them endangered invertebrates like the frittilary butterfly. Because coppice management has been a part of the countryside for so long, ecosystems have evolved to thrive at vary stages of regrowth. Maintaining a mosaic of various stages of woody regrowth thereby supports myriad herbaceous plants, invertebrates and other wildlife. In some cases, this grant funding simply supports the cutting of the coppice - the materials are left in the woody to decay with no consideration to the products they could be used to create. Often, deer nibble away at the young regrowth, stunting the regrowth and stressing the stools. While this strategy may be effective in providing habitat for the short term, it becomes clear that it's not a sustainable long term solution. Because this management is absolutely reliant on grant funding to sustain the coppice, the relationship seems tenuous in the long term - especially as we see a global trend towards shrinking budgets and ecologically-minded expenditures. Additionally, removing the craft from the system, erodes the ability for coppice workers to build an interested and engaged clientele who would otherwise help to support coppice management. Over time, it was the products and markets that actually created the impetus for and sustained the management of coppice. If we remove the very reason coppice came to be a relevant form of management from modern systems, is it possible to imagine it's perpetuation in an uncertain economic future? Rebecca pointed out the challenges of these inconsistencies in policy and has been addressing this tension in her work. Her book gives a good overview of the benefits of coppice, some of the existing management systems and species managed in the UK (hazel, ash, chestnut namely) and looks at a number of ways people can add value to these materials. Unfortunately our conversation was cut short but I felt grateful to her for sharing her time and thoughts so freely and look forward to speaking with her in the not-too-distant future. Soon Ben and I took to the road and headed back to Lodsworth for the afternoon. I took some time to explore the woods I'd come to know rather well during my past visits and measure some of the stand characteristics and regrowth. I went to explore the three cants most recently cut during each of the past three years. Much of the woodland Ben inherited almost 20 years ago was neglected and 'overstood' - or derelict. This means that some of the stools had died and the density subsequently declined - this in turn leads to a reduction in pole quality as they start to branch out more actively to fill in the available space. It takes some work to restore the coppice to what it once must've been. The chestnut stands on Ben's land (called 'Prickly Nut Wood' - a reference to the spiny husks that bear the chestnuts) were planted out about 160 years ago and were managed actively until sometime around the second World War. Probably having been cut once more between then and modern times, many of the poles are 6-8" in diameter and about 40-50' tall. Many of the stools have been cut higher than one typically would for coppice - 1-2' off the ground - and they have become habitat for a spectacular array of moss and lichen species. National conservation organizations have recognized this, naming his site a 'Site of Special Scientific Interest' which means that he must continue to manage them by cutting at their current height. This is less than ideal from a management perspective as stools cut low to the ground tend to encourage straighter growth, lacking the 'pistol-grip' formed base found on stems growing from a higher stool. Much of the regrowth I found was coming on quite strong. The chestnut put on a solid 6-7' of growth in the first season and once tired and overtaxed stools were showing considerable vigor. The best stocked cants featured stools at about 6-7' spacings which appears to be a particularly ideal interval for most moderate length rotations (6 to 25 years or so). For shorter rotations, it's possible to go for an even closer spacing - willow withies are typically planted somewhere between 1-2' from each other but are harvested every year. In many of Ben's stands, he'd done some significant thinning of the standard trees to open up more light for the coppice regrowth and maintain a more even structure. This generally amounts to about 6 or so standard trees per acre (a standard tree is a tree grown for timber within the coppice. It's characterized by an uncut, single stem). Not all of the stands recently cut were chestnut. The cant cut 2 winters ago features a polyculture mix of hazel, ash and chestnut coppice with oak standard overstory. The regrowth here proved strong though the stocking density was a bit low and could use some filling in so as to optimize productivity. To protect the regrowth from the pressures of deer browse, Ben erected a five strand temporary electric deer fence about 7' high around the perimeter. While it took a day or two to install the solar charged fence, it provides peace of mind and helps protect the vulnerable young regrowth. After about 3 years, the plan is to remove the fence wire, erecting it around the next stand, but keeping the rot-resistant chestnut poles in place so it can be fenced off again after the next cut. As far as numbers go, I collected growth figures on several stands at varying ages on his property. Stand 1 - about 17 year old chestnut regrowth - 4-7 stems per stool, 6-7' spacing between stools, ~ 40' high, individual poles averaging between 4-5.5" dbh (diameter at breast height). The lies on a 15-20% east facing slope with clay-loam soils. The canopy was dense with about 96% canopy cover. Stand 2 - 2 year regrowth. Between 10-20 stems per stool on average, 5.5-6' stool spacing, 10-11' high stems. Individual stems between .8-1.0" dbh. The stand lies on a northwest facing slope at about 20% grade. Stand 3 - 4 year regrowth - 8-13 stems/stool, 4-7' spacing between stools, 1.5-2.3" dbh. Northeast facing slope at about 30% grade. I finished up my day visiting stand 3 from above which is the same cant we'd cut when I was there as an apprentice 8 years ago. Ben has since cut this stand again after four years so its become highly productive after restoring the restoration cut we did in 2003 when the stems were about 18 years old, 6-8" dbh and 40-50' high. I joined Dave the apprentice, snedding up the cut poles with a billhook (removing the side branches and tops and grading the useful/non-useful poles). In the meantime, the other apprentice Mark kept busy cutting the rest of the standing regrowth. These poles were to be used for several purposes - the most pressing need was for baling stakes to pin straw bales together in their building work. Dave and I had a good conversation about his experience int he woods and goals for life beyond Prickly Nut Wood. After an hour or so, it was time to call it a day. We spent the evening together, sharing a meal and conversation while they concurrently put together a seed order for the coming spring garden. We were in Bed at a reasonable hour with Ben agreeing to take me to the railway station in Haselmere in the morning to catch my train to London where I'd soon be off for Limoges, France. On our way to Haselmere the following day, we took a moment to stop off at a nearby woodland we'd planted out with hazel when I was there in 2003. We had to scale a few fences to get there, traversing through a newly installed vineyard on the estate, enclosed in an impressive 8' deer fence. We encountered the property manager on the way who enquired as to who we were and what we were up to. Once he found out, he eagerly asked if we could tell him what we thought of the wood and what we'd suggest to do. He also mentioned they'd put pigs in with the hazel to fatten them up for a bit. As we approached the enclosed pig pen, we both were awestruck with the damage they'd done. Reducing the entire understory to a thick, deeply, barren muddy mess, it was absolutely evident that the lack of any 'management' here whatsoever, had led to a total destruction of the ground flora and soil structure. The results couldn't have been worse and in the long term may compromise the health of the hazel regrowth. Pigs in and of themselves don't have to be destructive, but when penned in and left to root around for an extended length of time, they can do incredible damage that may take years to rebound. That was definitely the case in this stand. We explored what we could of the stand and set off. In another 20 minutes we said our goodbyes and I made my way to London. I'll forever carry a deep respect and appreciation for Ben. He's a remarkable man - eager to experiment and innovate, with a long-term vision, a deep love for the woods and a lifestyle that supports his ethics. I continue to carry the inspiration that filled me when I first left Prickly Nut Wood and have integrated the lessons and lifestyle I experienced there into my own vision of a life built around the woods. This morning I left some time to sleep in (at least a bit) seeing as how I was still a bit 'knackered' from my red eye flight a few days before. The luxury of a comfortable bed is definitely not something to take lightly while on the road. I'd spoken with Martin Crawford at the Agroforestry Research Trust in Dartington, Devon the evening before and we'd pushed our meeting back till 2 in the afternoon which meant I had ample time to catch up and relax.