|

Hi folks Just wanted to spread the word about this upcoming event that may be of interest. E-mail us to reserve your spot. Hands-on Coppice Establishment and Conversion Workshop - Free! Saturday 2/25 - 10-4:30 The Sawyer Homestead, 556 King Pond Road, Woodbury Vermont with free public talk to follow from 6-7:30 at All Together Now - 170 Cherry Tree Hill Road in East Montpelier Join Mark Krawczyk (co-author of the forthcoming Coppice Agroforestry manual) and siblings Annie and George Sawyer at the beautiful Sawyer homestead in Woodbury, VT for a free, hands-on coppice conversion workshop Saturday February 25th. During this daylong workshop we'll begin to implement a management plan for a 7 year, rotational coppice woodlot, converting an existing 15 or so year old stand of red maple into a multi-purpose, polewood-producing forest stand. We'll spend the day felling polewood, limbing the produce, exploring potential value-adding opportunities, thinking about and discussing the design and layout of coppice systems, learning how to use a number of different traditional tools and techniques and have an opportunity to view the workshop of Dave Sawyer, master windsor chairmaker. This is a unique opportunity to participate in the development of a new expression of an ancient forestry system with lots of potential to help support and manifest homestead fuel and craft wood security on a small scale. We'll all likely learn something new about woodland management, value-adding processes, ecological design, and effective, efficient group work. Dress warm as we'll be working outside all day. If you have hand saws, a bill hook, loppers and clippers, or an ax, please bring. Bring a lunch (there will be some soup and bread) and we'll have hot beverages on hand along with plenty of core-warming work to keep you busy. Space is limited for this event so please contact us if you intend to come. Also, because the weather is difficult to project, we want to be sure we have your contact information in the case of inclement weather and a need to reschedule. For more information, e-mail Mark Krawczyk or call 802-999-2768. Best wishes and happy felling!

9 Comments

I've recently been re-reading and integrating some great historical ecological research on European woodlands into our manuscript and thought that the following two case studies might be of interest to our friends and kickstarter backers. There's some great detailed information in the profiles below which should prove invaluable towards helping us clearly design fodder based livestock systems here in North America.

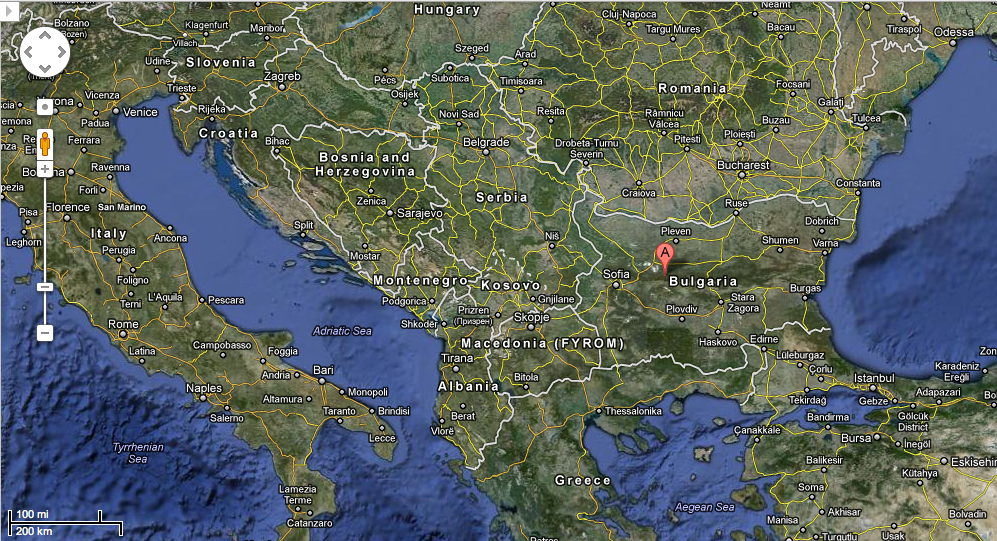

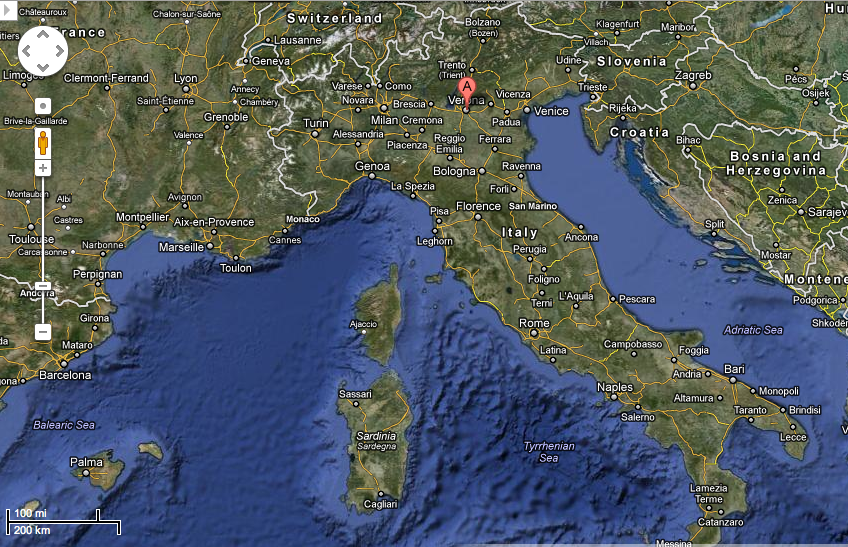

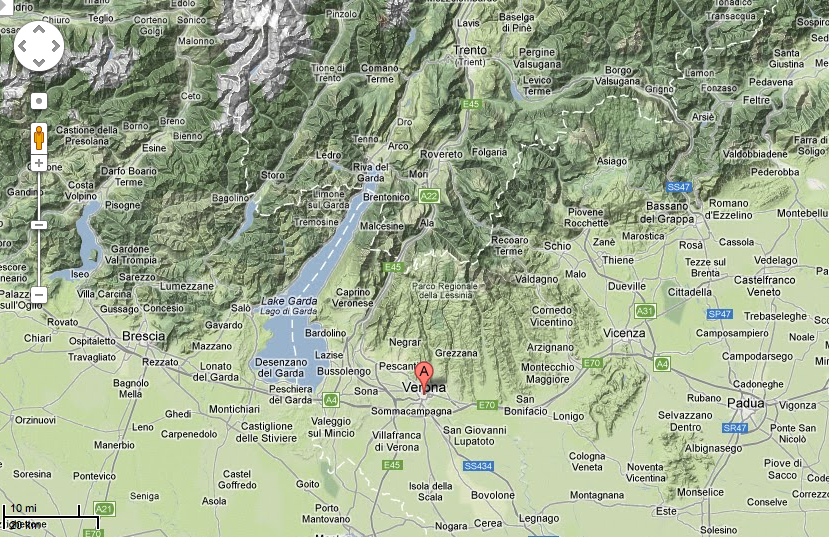

Enjoy! Mark Case Studies - Traditional European Wood Pastures Ribaritsa, Bulgaria The Bulgarian village of Ribaritsa, 10 km southeast of Teteven and 80 km east of Sophia, encompasses both level lowlands and steep slopes stretching 1970-2300’ (600-700m) above sea level. Enjoying a frost free period from mid to late April through late October, the lowest winter temperatures reach about 10℉ (-11℃). Receiving an annual average of 38.7” (982mm) precipitation, the highest monthly totals fall between April and early August, tapering off through the late summer and winter months. In this area, pollarded trees border many of village’s diverse dry meadows dominated by the perennial bunchgrass Chrysopogon gryllus. In July, farmers typically cut hay with scythes. In many Bulgarian pollard meadows, farmers give sheep and goats access to grass and browse both before and during hay making. The annual hay yield varies depending on the precipitation. Meadows average about 4,400 lbs (2000 kg) dry hay per hectare, though in productive years, it’s possible to manage two hay harvests, and yields may reach as much as 11,000 lbs (5000 kg) dry hay per hectare. Except for the ‘collective farm period’ (post World War II though the late 1980s) when meadows were fertilized with up to 175 lbs of N and P fertilizer per acre (440 lbs or 200 kg per hectare), the only fertilizer farmers apply comes in the form of manure. Farmers actually only pollard trees during dry seasons, when the hay harvest falls short of their needs. From mid-July through September’s end farmers harvest leaf fodder from hedge maple (Acer campestre), Norway maple (A. Platinoides), hornbeam (Carpins betulus), oriental hornbeam (C. orientalis), ash (Fraxinus excelsior), black mulberry (Morus nigra), oak (Quercus spp. - except for Q. cerris which is the animals do not eat), white willow (Salix alba), large leaved linden (Tilia platyphyllos) and elm (Ulmus spp.). Only in years of severe feed shortage do they use European beech (Fagus sylvatica), while black alder (Alnus glutinosa) remains even less common. They collect the nuts from hazel (Corylus avellana) and use the leaves medicinally to treat prostate problems and kidney disease in humans. Typically harvesting fodder on a 3-4 year rotation, farmers climb the pollards, severing leafy twigs 3.3-5’ (1-1.5m) long with an axe and piling them for later bundling. They tie bundles with a branch of the same tree or twigs of Salix alba or Clematis vitalba. They store these bundles, or leaf sheathes in a barn or on a platform raised 6.6-9.8’ (2-3m) heigh spanning between 2 trees. Two workers can harvest 141 ft3 (4 m3 or 5.2 yd3) worth of fodder a day. Unless annual hay yields fall well short of needs, farmers in Ribaritsa only feed leaf fodder to goats, providing cows, sheep, horses, mules and donkeys with hay. On average one sheep or goat requires about 220 lbs (100 kg) dry hay or 35 ft3 (1 m3) leaf fodder per winter. Valdagno, Vicenza, Italy Here we present a summarized case study of Elena Bargioni and Alessandra Zanzi Sulli’s article “The Production of Fodder Trees in Valdagno, Vicenza, Italy” from The Ecological History of European Woodlands edited by Keith Kirby and Charles Watkins. Their article offers a detailed look at the management of a small livestock farm in the Agno Valley of northeastern Italy. With a humid subcontinental climate and 58.6” (1489 mm) mean annual precipitation, the area experiences long, cold winters and hot summers with a broad annual temperature range. Located along the Agno River at an altitude of 2635’ (800 m) in the village of Castelvecchio, the farm’s soils derive from basalt bedrock and the steep slopes are prone to frequent landslides. The aspect of the farm’s various plots have clearly informed their use. Southeast-facing slopes were tilled, while meadows occupied the those aspects possessing less fertility, poor drainage and colder microclimates. The wood pastures and woodlands were largely relegated to the northwestern slopes. From the 1920s until 1992, the farm produced 1/3 of their annual fodder needs from managed pollards. Mainly comprised of ash (Fraxinus excelsior), but also including black alder (Alnus glutinosa), black poplar, (Populus nigra) cherry (Prunus spp.), maple (Acer spp.) and elm (Ulmus spp.), most trees were managed for fodder production with pollards distributed throughout the pasture either singly, in groups or in rows. Both individual trees and groups of trees usually lie scattered throughout pastures, whereas tree rows form property boundaries or divide tracts of land receiving different types of management. These rows of pollards with shrubs interspersed underneath offer the highest aerial productivity while occupying the least amount of space. The rows consist of ash pollards cut at 15-16.5’ (4.5-5 m) above the ground and hazel, hornbeam and Laburnum anagyroides are coppiced for fuelwood and browsed in the field during dry summers. Since farmers harvest branches every three years and coppice shrubs every two years, the semi-regular management helps minimize the impacts of shade on neighboring crops. Farmers prune the trees’ lateral branches, leaving 6-8” (15-20 cm) stubs called gropi starting 6.6’ (2m) from the ground and ideally spaced about every 20” (50cm) up along the trunk. Farmers often aim to create gropi so that they lie parallel to the tree row and along the inner side of the farmland property borders. Pollard regeneration occurs either from natural seeding or planting. Because pollards produce less seed and livestock browse many developing seedlings, natural regeneration is never completely sufficient. Shepherds often protected seedlings they discovered, surrounding them with thorny vegetation. The farmers raised 4 or 5 Burlina dairy cows, a local breed that produced 2.5 gallons (10 L) milk per day each, 25-30 chickens, a pig, and 2-3 sheep for wool. From November to May, the farmers carried feed to the cows in the barn which included harvested meadow hay, leaf fodder (known as frascari) and grass from the woods that they collected each day as needed. After the second hay mowing sometime between May and October, cattle grazed the wooded pastures and meadows. During drought years farmers supplemented feed rations with green leaves from shredded trees. Farmers harvested two types of fodder from pollards - broco - leaves from shredded/pollarded trees used directly as fodder (often from the thin branches of the crown), and frascari (essentially faggots) - branches and leaves that they harvested, dried and stored for use as winter feed. Farmers most commonly fed stock ash fodder though they also used alder, poplar and hazel fresh. Because beech often emerges early in spring before grasses have emerged, its new shoots provided a valuable early-season feed. Usually every three years, farmers harvest frascari with a billhook, or cortelon, during the second half of August. During the two years between harvests they pick the tree leaves and use them as feed. Farmers actually begin harvesting a pollard by first shredding leaves from the branches comprising the top of the crown, feeding them to cows fresh. They then cut fascari, leaving the stems on the ground to dry for a day. At this point the shoots stretch about 5’ (1.5 m) in length. They then bundle the harvested frascari stems into faggots 10-12” (25-30cm) in diameter and bind them with shoots of Laburnum anagryoides. They leave these faggots standing in the field for another 2-3 days before piling them flat in crisscrossed layers in the barn for storage. It takes 3-4 hours to collect fodder from a single tree, and the case study farm retains 200-300 fodder trees. Each tree produces approximately 17.5 ft3 (1/2 m3) fresh leaves and 8-10 faggots. Annually 85-100 trees produced between 700-1000 faggots. Before feeding to livestock, farmers leave the fodder out during the morning hours to absorb moisture. They then shred the leaves from the branches and feed them to the cows, saving the twigs for fuel. Each cow normally consumes one faggot per day. A productivity analysis of conventional pasture versus wood pasture found that on a hectare for hectare basis, the mix of feed produced from pollarded wood pasture supports one more cow per hectare (0.4 more cows per acre) than feeding from a landscape only producing hay. A couple of weeks ago I had the opportunity to visit my friends, the Sawyer's, at their family homestead in Woodbury, VT. I first heard about Dave Sawyer six or seven years ago - his reputation preceded him as an immensely talented, kind, and knowledgable green woodworker, known especially for his mastery of the art of windsor chairmaking. (Check out some of Dave's work at http://www.windsorchairresources.com/sawyer.html). In fact, Dave helped inspire the work of my woodworking teacher Drew Langsner in North Carolina in the early 80s.

I first had the opportunity to meet Dave a few years ago, visiting his home and workshop. I was impressed with the quality of his work and the modesty with which he produces it, most definitely embodying the spirit of a traditional woodworker, living a simple life that revolves around the things that are truly important in life. Sometime thereafter I met his daughter Annie, who completed a Permaculture Design Course this past summer at Prospect Rock Permaculture, co-taught by Keith Morris, Lisa DePiano, Alissa White and myself. Having grown up on the Sawyer's land, Annie has a deep connection to the property as well as to the skills that make it possible to live a life in relationship with what it has to offer. Annie had previously mentioned to me that she and her brother had been planning to initiate coppicing of an existing stand of red maple, and her final design project for the course included this as an integral part of the site's productive capacity. I was intrigued and agreed to come by for another visit the next time I was in the area. Months passed, and I recently had a good excuse to take a slight detour and examine the stand more closely. I arrived to find a 3-4 acre plot. largely dominated by red maple, with significant potential. Annie and her brother George escorted me throughout the stand, describing the site's history and their vision and needs. Red maple (Acer rubrum) is an exceedingly common eastern tree species that often naturally exhibits a multi-stemmed. It undeniably lends itself to coppice management. Unfortunately, the species proves to be less-than-exceptional for most applications. With a density of 34.4 lbs/cubic foot (as compared to 52.5 for black locust - the densest species growing in the northeastern forest) and 18.7 million BTUs per cord (as compared to 27.7 for hickory), it's a relatively lightweight species with a moderate value as fuelwood. The wood proves to be poor in decay resistance, offering little long-term potential for outdoor uses. But... it grows and gives of itself freely. And as I like to say, 'When God gives you red maple... you make (insert useful function here)!' What I'm getting at is that while not exceptional at any particular function, red maple proves to be well suited to the site, and as such, it makes a lot of sense to use it - especially when their needs are fairly straightforward - building poles (for roundwood structures, yurts, tipis, etc; and fuelwood). This particular stand appeared to be just about optimal for conversion to coppice management. Largely east-southeast facing, the existing trees were closely spaced, with individual stems often between 6-10' from one another, and relatively young (Annie and George, in their mid-late 20s, explained that the stand was an open field during their youth, having been left to the process of succession sometime in the last 10-15 years), they should respond well to cutting and prove to be productive, with only a moderate need to fill in gaps between individuals to help increase productivity, and encourage straight, upright growth while outcompeting herbaceous vegetation in the understory. The landscape also provided some very useful topographical patterns that clearly suggested boundaries between individual cants (contiguous areas of coppice). Based on their needs and the existing growth on the site (about 4" dbh after roughly 12 years growth), we decided that a 10 year harvest rotation seemed to make the most sense to provide them with the materials they desired. Thus, we were able to break up the stand into 5 separate cants, approximately 0.4-0.5 acres in size that they could clearcut every other year to provide a polewood and fuelwood yield. The stand also featured a number of more mature existing trees having persisted for a few decades prior to the succession of the field. These included a number of sugar maples, black cherry as well as red maple. We discussed leaving these as standards - depending on their location (relationship to the to-be-coppiced red maple) probably 4-8 per cant - that could be grown on for lumber and/or maple sugaring. To optimize the productivity of the coppice regrowth, we talked about starting by cutting the cant along the southernmost edge of the stand and progressively working north (upslope - see attached photo with cant boundaries - note that the stand marked 'cant 4' lies at the high point of this portion of the property) so as to maximize each stand's access to incoming solar radiation and minimize shading from more mature stands. In terms of access, they had already created a rough primary road running roughly east-west up the slope which provides truck access to much of the stand - and an existing 'terrace' that appeared to be the remnants of an old farm/logging road running (north-south) through the southern portion of the property could be reopened and expanded to provide a stable extraction route for harvested polewood. In parts of the cants where growth was a bit more sparse, we discussed either layering in coppice shoots after they've begun to grow, 'stooling-up' individual stools to produce rooted clones for transplanting, or introducing new species to the stand to further diversify the mix and further support their needs. (They were particularly interested in black locust [Robinia pseudoacacia] for fencing and building materials and fuel). Probably one of the biggest challenges to coppice establishment will prove to be deer browse, as they've already seen clear evidence of their presence on the site. We discussed the options, and while fencing seems to be the only 'sure' form of protection, they may likely elect to take a wait-and-see approach before making the investment. This will definitely prove to be a challenge for most folks implementing coppice management on their homesteads, and it's something we'll discuss in detail in our book. In addition to the quality and accessibility of the existing stand, probably the most promising aspect of the Sawyer's property is their eagerness to engage with coppice and the immediate needs it will serve for them. It will most definitely prove to take time and energy to transform the stand to its true potential, but it's clear that Annie and George are up for the task. To help them along in the process and also provide an opportunity for others to explore the design, establishment, harvest and management of a developing coppice stand, we've agreed to host an open work party/workshop over a to-be-determined weekend in February during the course of which we'll harvest 'cant 1', limb the harvested polewood, discuss value-adding potential and green woodworking skills, and explore the practical aspects of coppice stand design. Once we've selected a date and have more details, we'll post an update - it will definitely prove to be a strong, practical, hands-on opportunity to engage with coppice. In the meantime, Dave and I would love to hear about projects any of you may have in the works - we're continuing to pour our lives into the manuscript and species database, and the broader the breadth of practical experience we have to draw on, the better. Thanks so much to you all and happy solstice! Mark I went to my daughter's college choir's Lessons and Carols performance yesterday in Middlebury, VT. One of the readings about the predictions of Christ's birth included Isaiah 11:1: "There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots . . ." Whoa! I thought. That's coppice! Coppicing and root suckering both!

When I got home I called my mother to check on her after her surgery last week. I told her of the reading, and she about hollered! She had been in Bible study the week before and they read the same piece. What's more, she read to me out of their Bible study companion manual. It turns out that the word for coppice in Hebrew is something like 'netzer', and it is believed that the name 'Nazareth' derives from that root word 'netzer'. As the place where Mary was told by the angel she would bear the baby Christ, this is appropriate for a name, given the prophecy. It also reveals how deeply coppice culture was embedded in pre-industrial, pre-hydrocarbon cultures--everyone used to understand the symbology of "a shoot from the stump of Jesse," or they wouldn't have used the symbol in the prophecy of Jesus' coming. This can only mean one thing: If you love Jesus, then you must love coppice too, because he was a shoot off the ol' stump! Happy SolstiChristmaHanuKwanzaaNewYear everyone! Dave Hello friends

First, though we're formally one day late, both Dave and I want to extend our deepest, most heartfelt thanks to all of you for the support you've given us, both via kickstarter, as well as during our evolving research and writing phases. You have truly helped propel this project along, and we are forever grateful to place ourselves within such a powerful demonstration of community support. We both realize it's been quite some time since our last update, and felt it was high time to check in. As we settle into the cold months of the year we both have thankfully begun to find a lot more space in our schedules to refocus on the development of Coppice Agroforestry. While Dave and his wonderful assistant, Daniel Plane, along with several other hard working volunteers, have been diligently amassing details on the wood qualities, growth characteristics, medicinal uses, and fodder values of nearly 600 species of woody plants, I've been diving deeply into the literature to see what additional insights and information I can find to further flesh our our growing manuscript. What this means is that I've spent the past 3 months reading through a wide range of resources relating to forest management, woody plant physiology, craft work and value adding and more, pulling out the most pertinent gems which I'll next work to integrate into our manuscript. It's been a pretty monumental process, and I feel like I've only just begun to explore the mass that lies beneath the iceberg's tip. The blurred photo below shows the stack of books I've poured through so far. Just two more books - Ecoforestry and the Ecological History of European Woodlands - and I'll start to dive into the vast sea of academic research Dave and Daniel have amassed. For folks who are interested, I'm including a brief write up of some of the highlights to date... Once again, thanks so much for your support, eagerness, patience and positive energy. We are honored to serve you and are excited to continue with this ever growing project! Mark and Dave Working with Your Woodland - by Mollie Beattie and others - Written in the early 1980s, Working with Your Woodland is the most approachable, comprehensive and well written book I've come across that explores the nitty gritty details of small scale woodlot management. Largely geared more towards forest management in non-brittle, cold temperate climes, the book covers a broad breadth of topics including the history of the northeastern forest, a suite of forest management strategies, the economics of woodlot management, the component parts of forest management plans and more. It's a great read and likely available as a used book on-line. While it pays little if any lip service to coppice growth, it does lay a strong groundwork for well-informed approaches to appropriate forest management. The Forgotten Crafts - by John Seymour - This coffee table-esque resource is gorgeously illustrated and a delight to peruse. With individual 'chapters' (usually 2-6 pages each) covering well over 50 traditional crafts, the longtime author, researcher and purveyor of self-sufficiency skills creates a highly readable and clearly illustrated resource that explores the historical context of each craft, some of the details of material procurement, harvest and management, as well as just enough information to develop an understanding as to how products are made. This book features a strong emphasis on coppice crafts but also explores complementary crafts that relied on sustainable woodland management in some way shape or form (tanners, wheelwrights, etc). The Book of Masonry Heaters - David Lyle - Also published in the early 1980s, The Book of Masonry Heaters offers a remarkably comprehensive (though perhaps somewhat dated) exploration of the subject. Starting with a history of human's relationship with fire, the book describes the evolution of our relationship with wood heat, finally exploring in-depth, the stove designs and construction details of masonry heaters from cultures throughout Europe and Asia. For those folks interested in exploring coppice management for fuelwood production, the link between coppice wood and masonry heaters is a match made in heaven. Well-illustrated, this book covers the breadth of this fascinating subject, making the information accessible and easy to digest. Hey everyone!

Sorry to have been so remiss in updating you all about our work on Coppice Agroforestry! Here is a little piece about what I’ve been focusing on to keep your appetites whetted. I have been working on the coppice species database, along with my friend Daniel Plane. We have amassed a large quantity of information on a growing number of species—currently 593 mostly-temperate trees and shrubs. We have researched the ecological characteristics (size, form, habit, site tolerances and preferences, behaviors, etc.), timber uses and qualities (wood uses, durability, hardness, specific gravity, color, shrinkage potential, etc.), basketry potential, and medicinal uses (parts used, actions, indications). We have the barest of beginnings of research on edibility of these species, and we intend to do a thorough search of ethnobotanical literature for that information, but also to see how the native Americans used these species, since they were more likely to be using small diameter wood than timbers. Every time we turn to a new arena of research, we find species we add to the database, so we have about half of the species without all the previously researched data filled in! This database alone is a huge project, but the result will be quite useful trove for folks to pull info from. We expect to prune and thin the number of species as we go back to fill in the gaps, depending on their characteristics and how much data we can get for each one, but we still find ourselves in the expansion phase of database creation. Soon, though, we hope to enter the consolidation phase, then the pruning phase, and then the final formatting and editing after that. We have also embarked on an ambitious project of deep scientific literature review to seek data on the use of these species as fodder for livestock. I have already found over 65 papers from around the world documenting the nutritional value of some species for livestock. However, not all of these papers are that useful to us. Some are poorly designed studies, some deal with species of lesser or little interest for this book, some are too narrowly focused to offer us much more than leads to other papers in their reference sections. However, we will persist, as we have yet to follow many leads we have discovered so far. One thing I wanted to turn your attention to on this score is the following website: http://www.fao.org/WAICENT/FAOINFO/AGRICULT/AGA/AGAP/FRG/MULBERRY/DEFAULT.HTM This set of UN Food and Agriculture Organization pages has a bunch of papers from around the world on the use of mulberry as animal forage. The results published in these papers and posters are pretty phenomenal! If it were only one study, they would be hard to believe, but time and again, in different countries and with different researchers, white mulberry (Morus alba) turns out to be an amazing fodder plant. This species can produce yields of 8,000-11,000 pounds of forage per acre (all in the tropics; the highest documented yield: 35,000 pounds per acre!), with the leaves being nutritious and highly palatable to cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, rabbits, chickens and silkworms. The crude protein content of white mulberry ranges in these studies from 15% to 28% (compared to 13% for alfalfa hay!). This species will coppice, it will pollard, you can probably shred the foliage from the trunk and have it regrow. It does need a lot of fertilizer to achieve such yields, but Italian researchers have shown that growing mulberry with subterranean clover makes a huge difference in yield without fertilizer. And you can plant pollard trees in your grass pasture and actually INCREASE the pasture productivity due to cooler temps in the grass! So this is but one slice of what we are up to, and probably the one web page with the most useful and mind-blowing information we have found so far on coppice-able fodder crops. We need people in the temperate areas of the world to play with this species, among many others, to see how it performs in our climates and soils. We also need some help on this project! The fodder research, in particular, is very time consuming and not yielding a lot of data for the time put in, at least yet, but we are determined to do the best effort possible to gather the most data we can. If anyone out there wants to help do some of the literature searching, we need people to search for various strings of search terms on Google Scholar—and ideally at University libraries with good academic search engines and article access—for every species we have in our database! If you are willing to put in a few or many hours doing this work, please get in touch with us at [email protected]. We are also still accepting donations to support this work. You can mail checks to Dave Jacke at 308 Main St. #2C, Greenfield, MA 01301. We will honor the same schedule of rewards as posted on our Kickstarter page. Thanks so much for your support and interest! We look forward to hearing from you and getting this critical information to you in what we hope will not be the too-distant future! Saturday and Sunday March 12-13 - Skopje, Macedonia

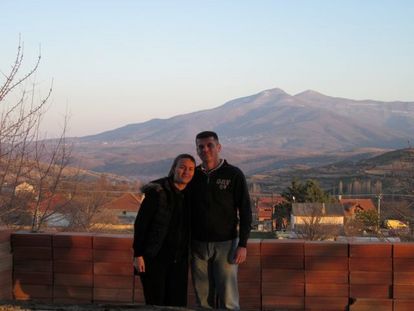

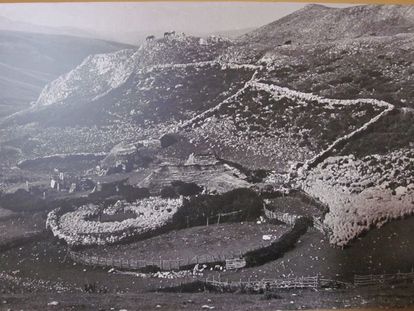

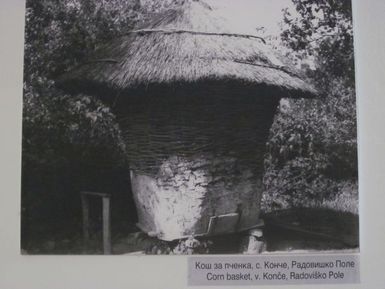

Apologies folks for such a long delay since our last update. Spring has returned here in the northeast with a vengeance and thrown off a few of my earlier established update patterns. Just a few more installments left recounting Mark's trip in Europe. We're still plugging away at the book and will continue to keep you all abreast of what we're up to and thinking about. Thanks for your interest and support! ~~~~~~~~~~~~ With a meeting planned in Thessaloniki, Greece on Monday morning, I’d planned to spend the day in Skopje on Saturday and then head south to Greece on Sunday. I was grateful to have a slow morning to sleep in a bit and relax after such a thoroughly full week. Around noon we headed to the surrounding countryside where Martinka and Ilija had recently purchased land and are in the process of building a house. The south facing lot, about a half acre in size, included nearly a dozen walnut trees, several cherries, and a modest vineyard. Located on a gently sloped hill, they enjoyed beautiful views of the mountains off to the south. It was a lovely, warm sunny day and we all sat out on their soon-to-be porch, soaking up the sun after sharing coffee and some snacks and eventually dozing off for a bit. It felt absolutely luxurious. We talked through one of their big site design challenges - creating sheltered protection from the surrounding neighbors. The drawback to their exposed, mid-slope perch is the fact that they are more or less on display up there for neighbors and passers by. We discussed layout and species selection for a multi-functional hedgerow to create a privacy screen without compromising the view of the mountains they love. As the light began to fade, we continued along the valley and stopped at a centuries-old monastery. The architecture was absolutely reminiscent of that at Rila in Bulgaria - just quite a bit smaller. Within the complex, the property steward ushered us over to a small museum where they had a modest but intriguing display of several traditional tools, exquisite Macedonian dress and the millworks that was once in operation here along the river. It proved to be a short but enlightening side trip. That night, I’d planned to solidify my travel plans to Thessaloniki, grateful to have the assistance of a native speaker/reader of the Macedonian language. Martinka helped me navigate the railway’s web page, eventually choosing to call the station instead. We were equally awestruck when the operator told her that train service to Thessaloniki from Skopje was no longer in operation. I had just done the same trip not even a year ago, but it turns out the service had been canceled just one week prior. We then learned that the only option for me would be to wait another day and take a bus that left early Monday morning. Though I’d already reserved a hotel in Thessaloniki for Sunday night and had planned a morning meeting there on Monday, there was little else we could do. Fortunately, it turned out that the bus was scheduled to arrive by 10:30 (assuming all went smoothly at the border) which would leave me with a half an hour to make my 11am meeting. Ilija and I ran across town to secure a ticket for the route to make sure I wouldn’t get shut out of plan B. While I hadn’t anticipated another day in Skopje, it was pretty easy to make the most of it. I started off another lovely day, walking towards the central promenade in town. Being a Sunday, things were quiet and calm in town. I strolled along the main pedestrian street and found a cafe with outdoor seating to soak up the sun and the culture that steadily passed by. From there I walked across town, heading to the other side of ‘the stone bridge’ where I found the narrow, windy streets of old market (which is still a marketplace today). Relatively touristy, the place was full of restuarants, cafes, and shops of all sorts. I explored for a bit, getting more or less lost in the windiness, eventually emerging at the food market where I disappeared for a while, meandering amidst fruit and vegetable stalls, trinkets of all sorts, a gruesome diversity of fresh cut meats and a bustle of activity. My original destination had been the Macedonia Museum, so soon enough I tried to modify my trajectory towards the grounds. From the exterior, it was difficult to tell if it were actually still operating. The grounds were overgrown and the building appeared gray. But once I entered the space, I found the best and most relevant collection of artifacts and exhibits I’d seen on my trip. Covering archaeology, iconography, agriculture, traditional building, crafts, clothing and more, I spent several hours exploring the facility, snapping dozens of photos and reveling in such a treasure trove of fascinating information. I highly recommend it if you ever find yourself in this fine city. As pictures are worth at least a thousand words, I’ll save us all the text and leave it up to them. Friday March 11 - Mark in western Macedonia I woke up at what I thought was 7:45, leaving myself a few minutes to prepare before Ljupcho came to pick me up around the corner at 8. I found Ilija in the kitchen where he offered to make me coffee. I gladly obliged, though steadily saw the clock ticking away, growing closer to 8. A minute or so before, I told him I was probably going to have to hurry as I should probably head outside to meet my ride. He looked at me surprised and said, ‘I thought you were getting picked up at 8’. This is when it finally hit me - I’d been an hour early for everything for the last three days. It was so relieving to realize that I’d suddenly gained an hour of life - and a most relaxing hour at that. Ilija ran out to pick up some breakfast - burek - a delicious, flaky, coiled, cheese (or meat or spinach) filled pastry that I’ve learned to absolutely love. He talked a bit about his work as a lawyer and he shared some very interesting insights into the history of the Republic of Macedonia and the relatively recent transition from Communism to Democracy. This entire region is highly complex with a long-ranging, dynamic and varied history. Disputes over borders, centuries of occupation, a wide diversity of languages, cultures and religions all contribute to the dynamism of this ecologically rich region. At 8, I went out to meet Ljupcho and we headed across town to pick up Pande for our day trip to the western side of Macedonia. This was somewhat familiar territory for me. Almost a year ago I’d spent a few days there at the end of a trip to Greece that was sparked by a an opportunity to teach a natural building class there. We left Skopje and soon approached some of the highest mountains in the country, heading south along the foothills until we had no choice but to climb. Our first stop was a place called Mavrovo - a mountain town and more recently, a national park. At these high elevations, most of the forests consist of either beech or coniferous species. As we reached the entry of the park, we pulled over to examine an extensive beech stand. Apparently human pressure on this landscape was significant up until the development of the national park. Fuelwood harvest and large sheep populations kept the forests in a largely stunted state. At this point, the wood-pasture-type stand featured beech pollards that were about 10’ high, 3-4' dimeter and had a very low quality stem - basically useless for lumber. The forest management plan sought to convert this degraded wood pasture into a high forest over the course of 100 years. They first cut the trees between 1965-70, allowing the beech to coppice. Five years ago, they went through the stand, thinning the stools down to single stems with the long-term vision of converting the stand to a seed-originated forest. Because the forest lies within the boundaries of a national park, the scope of their management is limited. Mavrovo National Park covers 73,000 hectares, has 400 km worth of trails, and 70 employees. The park’s forestry office oversees forest management, hunting, wildlife management and tourism. They harvest 18,000 to 20,000 m3 fuelwood per year, marketing it to locals, log companies and retail outlets in the town of Gostivar. Because of the access and management challenges due to the snowpack, they carry out felling operations fro May-November (and because they aren’t managing for coppice growth). We spent a half hour exploring the park, stopping to enjoy some majestic views out towards Albania, just beyond the ridge of the highest peak in Macedonia. The snowpack made the roads and trails relatively difficult to traverse this time of year, and there really wasn’t any coppice to see, so we turned around and headed south. It was very interesting to me to re-explore this landscape with two well-trained locals. When I’d visited western Macedonia in 2010, I was completely oblivious of the fact that the vast majority of the forests I was looking at were managed as coppice. The longer rotation lengths and the expansive extent of the stands helped them blend into the mountainside. This time, I understood that most of the mountains were blanketed in coppice cover and likely had been for the past few centuries. About 10 miles down the road, we pulled off to examine a large clearcut of a nearby oak stand as well as some of the more recent regrowth in the stands adjacent to it. The first area Pande and I looked at was a four year old sessile oak (Quercus petraea) stand. The stems were 1-2 meters in height (3.5-7’) averaging about 1.5 m. Stools contained between 6-12 quality stems that were approximately .8” diameter (ranging from .5-1.3”). Pande explained that oak coppice typically produces a considerable number of stump sprouts at an early age (10 or more), but by the age of 15-20, they’ve typically died back to one or two. As we examined the stools in the stand, we noticed that some were markedly larger than others and the smaller ones tended not to display much in the way of remnant stumps around the stool. As we examined these smaller stools more closely, it appeared as if they were actually root sprouts - not stump sprouts. The more we looked, the more common this pattern seemed to be. The healthiest, most vigorous sprouts all emerged from a clear stool base where several stumps still remained - they were easily twice the size of those clumps emerging from root sprouts. This seemed to be an observation new to Pande as well. Several other coppice compartments bordered this stand so we could compare their respective rates of growth and stocking quite easily. In a stand close to the road that was probably closer to 20 years old we found clear evidence of locals having cut and removed the sprouts from entire stools interspersed relatively randomly within the coppice. The deleterious effects of this was plainly visible - stuck in the shadows of a near-closed canopy, these poor oak stools showed little more than a few sickly, near-dead sprouts, and at this point were likely dead and lost. On the other side of the highway, I took 15 minutes or so to explore the regrowth of a ten year old oak-hazel stand. It was great to see a mixed stand, as most of the coppice systems I’ve seen to date were relatively monocultural. The hazel had come up very strong but it was hard for me to imagine what useful ends the state forestry department would have for this oh-so-useful craft material. The oak stools were spaced about 4-6’ from one another, with scattered hazel mixed in throughout. The oaks featured between 2 and 6 stems per stool and were about 15-18’ tall. Average diameter was about 2.25”. Individual hazel stools had far more stems - between 11 and 16 on average - and average about 1” dbh. Long and straight, they would be a very high value product if there were a market for woven hazel crafts. We got back in the car and continued to head south towards the town of Kichevo. Soon enough we had descended from the mountains, reaching a spreading valley just before the town. We pulled into a parking lot at the northern end of town where we met the directors of the local Forest Enterprise Unit. After exchanging greetings, the five of us crammed into a Lada 4x4 and continued along to the mountains southwest of the settlement. It was a beautiful bright sunny day and after about 20 minutes we reached our destination. Our first stop came along the low slopes of the hillside where we found a southeast-facing (25-30% slope)twenty year old mixed stand that featured an impressive diversity of species. While oak dominated the stand, ash, alder, lime/linden, hazel, apple, wild cherry and Cornus mas all could be found within a radius of 50 meters. The oak stools possessed between one and four stems per stool with stem diameters averaging about 3-3.5” with the largest reaching 4.6”. Ash stools tended to have more stems - 4 or 5 - while their diameter averaged about 4”, ranging from 3.7-4.35. At two different points, I found stand densities of 90 and 120 square feet of basal area per acre. Though the stand wasn’t particularly photogenic, and it wasn’t the prettiest woodland to the eye, I was delighted to have had an opportunity to see such a diverse and mixed stand. One of my personal reservations about many of the coppice systems I’d seen in the UK was their ‘monoculturality’. While I can appreciate this structure from a ease of management perspective, ecologically speaking it makes for a bland, simplistic ecology. As I’ve read, most coppice stands were developed from what were once diverse, mixed woodlands, gradually converted towards an even-aged coppice structure. I imagine that many of the systems I’d previously seen were either the result of planting initiatives or generations of selection with the intention of creating a more pure stand. It’s great to see that there are examples of working multi-species stands. We then continued on up the hillside to explore a ‘reconstructed’ (converted) turkey oak (Quercus cerris) high forest. Our hosts began working to convert this stand about 7 years ago. Covering about 150 hectares, the ‘singled’ standard oak trees are now about 60 years old. The management plan calls for harvest of the ‘mature’ oaks on a 100 year cycle. At another mixed stand occupying a steep, southeast facing slope (42% grade), lime/linden, hazel, wild cherry, ash and Cornus mas all comprised the forest understory. The singled oak trees were about 15’ from one another and measured 10.5-13.5” dbh. I measured a stand density of 90 square feet of basal area per acre. While a clever observer would make out the swoop at the base of the oak trees that indicated their former management as coppice stools, without that partially hidden clue, it would be hard to recognize the history of this stand as anything other than a natural, uneven-aged, seed-originated forest. We explored the woods for a half hour or so, walking downslope to a log landing adjacent to the lower section of the road we’d arrived on. Examining the leaf litter and organic layer of the soil, I found a healthy mycorrhizal fungi mat. It seemed like this forest was well on it’s way to adding more structural diversity to a hillside that had been managed solely as coppice for the past few centuries. We drove back to Kichevo and sat down for a late lunch at a local taverna. I’d become accustomed to this pattern by this point and settled into a comfortable seat where we shared food and drink for a couple of hours. Our hosts recommended I try a local specialty for which I’m grateful. Deliciously spiced house-made sausage and a massive hamburger-like ground beef patty. Following a lovely first course of fresh salad, the food was amazing as usual. The afternoon had grown late and we dropped off our local forester hosts before making our way back to Skopje. Ljupcho and I carried on an impassioned conversation about our respective views on the economics of forestry systems and my reflections on the management strategies I’d seen during my trip. While we didn’t see eye to eye on everything, I’m hoping our personal philosophies may have influenced each other to view the practice with a more comprehensive eye. As we arrived back in the city, I did my best to express heartfelt gratitude to Ljupcho and Pande for their gracious guidance, freely shared insights and remarkable generosity. The past three days literally felt like weeks, and I knew I’d continue to revel in the light they’d helped shine on our project for quite some time. Thursday March 10 - Mark in Radovish, Macedonia

We awoke to a clear sunny day (me, an hour early yet again - forgot about the time change) and enjoyed a morning coffee before packing up and saying goodbye to our host. Today I anticipated the routine, so I felt much more prepared when we reached the Forest Enterprise Branch office for the Radovish district to meet with the regional director. The branch office here was considerably more modest than that of Strumitca - the director only had 3 phones strewn about his desk. We made small talk while someone fixed us coffee and the director took a few minutes to personalize leather-bound notebooks as a gift for each of us to remind us of our visit. He was a very eager man, lots of energy and enthusiasm - and for some strange reason, he seemed to take a liking to me. Though he spoke no English, I learned a fair bit about the context of the forests in this part of Macedonia. Covering a total of 40,000 ha (36,000 state owned, 4000 private), their regional forests are divided into 7 units. About 11,000 of these hectares are high forest, 22,000 coppice and 8000 shrubland. In addition to their development and administration of management plans for state forests, they assist private owners to manage planning, marketing, and felling operations. If private landowner has more than 100 ha, they must develop a management plan. This is relatively rare though as most private forests average about four hectares in size. Here most of their forests are beech. They cut about 30,000 m3 annually, 20,000 in firewood which is about 50/50 oak and beech, and 10,000 m3 worth of beech logs for lumber. In this region they afforest (plant) about 30 hectares each year, again typically in gaps within forested lands. Since 2008, they’ve planted out 250 hectares in primarily Robinia, Quercus, Fraxinus, Aesculus (horse chestnut), Pinus nigra, and Acer pseudoplatanus, all of which will be managed as high forest. They focus their plantings within headwater zones for erosion control in response to flash flood events in previous years. Like most of the country, the region was under the rule of the Turkish empire for 500 years, during which huge areas were cut and used. Historical accounts from the15th,16th, and 17th centuries state that most of Macedonia was then covered in coniferous forest. Today, there's less pressure on the forest from people and animals, so much so that since 1945, forest area in Macedonia has about doubled thanks to forestry, urban migration and reduced human impact Our field trip in Radovich took us up into the mountains to explore the beech stands there. At the mid-elevation slopes we found forests with a similar stand structure as those of the previous day - oak/juniper on overgrazed lands and primarily oak on the non-grazed lands. We stopped briefly to observe an oak stand that was clearcut 15 years ago. They said that before the cut, the trees were relatively low quality and stunted. A few individuals were left near the road demonstrating their size and quality or relative lack thereof. Today, the 15 year old coppice regrowth is about 30’ tall, virtually the same size as the uncut stems near the road. A testament to the invigorating effects of vegetative reproduction. At our second stop, we looked at a beech-dominated stand cut 25 years ago. This stand also included some scattered birch (Betula alba) as well as some pine and Doug fir which were planted in an attempt to diversify stand structure and species. The forest managers are somewhat concerned that the shade-tolerant Doug fir may cause a problem in the future if it is able to effectively establish itself from seed, as it will likely outcompete the pine, beech and birch. Time will tell. Next we took a look at another coppiced stand of sessile oak (Quercus petraea) which they plan to continue to manage as coppice. Apparently, they thin the stand after about 30 years of regrowth, reducing the number of poles on each stool by half, from about 7 stems to 2,3 or 4. This thinning works because the material harvested is useful as fuel and thus provides payback for the operation. Finally, we looked at some relatively mature beech coppice of which there are about 8000 ha total. At the higher elevations, between about 1000-1300 m, we reached a 3000 ha uneven-aged beech high forest. This hasn’t been coppiced and will likely continue to remain as such. These high elevation forests feature relatively deep snowpacks and compromised access. Because they aren’t managing them as coppice, they do most of their felling and extraction from May-August. They usually have some snow cover by September. These beech stands are quite productive, yielding around 200 m3/ha. Our field trip culminated at a house/hall built by the local Forest Enterprise Branch amidst the beech high forest around 1300 meters. Here we enjoyed the long views and then retreated indoors for a celebratory meal where we were joined by 10-15 forest workers who seemed to live and work in these upland forests. It was quite a cultural event that spanned several hours. It was almost as if the platters of salad, meat, cheese and bread responded just like coppiced broadleaf trees - every time they were cleared, they came back full as ever. Our hosts finished the afternoon with loud, joyful celebratory song, none of which I understood, but they seemed to be well known local tunes dear to their hearts. What a full and wonderful cultural experience. We eventually found a way to politely slip away from what appeared like it might be an all day affair and descended the mountain. From here, Pande, Ljupcho and I were to head to Macedonia’s capital Skopje and Tzvetan and Georgi back to Bulgaria. We bid each other appreciative adieu’s and went our separate ways. I truly look forward to continuing our friendships and feel amazingly fortunate to have been able to connect with such wonderful, brilliant people. The landscape changed dramatically as we headed northwest, soon enough giving way to lower rolling hills almost completely devoid of tree cover. These drylands were likely once forested, but the legacy of intensive land use and overgrazing now bear a completely different landscape that supports agriculture, despite the saline soils and very limited water reserves. I’d made a connection on-line with a kind couple in Skopje who are actively interested in Permaculture and were willing to host me for a few days. I got dropped off just around the corner from their house and we headed out for dinner to get to know one another. I still had one day of Macedonian coppice-related site tour to go…. Wednesday March 9 - Mark in Strumitca, Macedonia

It was eerily quiet as we started our day Wednesday morning. The lack of virtually any activity on the small city’s streets was the only visible remaining sign of the previous night’s festivities. I woke up a bit groggy and packed up my things as it sounded like we were planning to head north later in the day bound for a new destination. Thinking I was late by five or so minutes, I rushed downstairs with my bags only to find the lobby empty. Worrying that I was late enough to have missed them getting a start on the day, I asked the hotel manager if he’d seen any of my party yet. He pointed me outside where Pande enjoyed a cigarette and espresso with one of the hotel employees. It was three days before I learned that we’d gained an hour back when we entered Macedonia so I was consistently one hour early for everything - funny once I finally figured it all out. Pande is a wonderfully warm man. Handsome and moderate in build with tight, curly greying hair and a warm smile. While he’s conversational in English, he was clearly far more comfortable speaking his native tongue so we unfortunately didn’t get to enjoy the depth of conversation we otherwise might have were either of us more adept in speaking one another’s language. We eased our way into the morning. To me it seemed like a leisurely start on the day - what my Greek friends might refer to as ‘Greek time’. But in retrospect I now think that everyone was likely to have been right on time. We left our things at the hotel and headed off somewhere - I wasn’t quite clear where yet. We passed through across the parking lot, through the corridor, hung a left and entered a non-descript building, ascending the stairwell and landing on the second floor. I still didn’t know where we were or why we were there but it seemed like something moderately official. We were warmly greeted by the office staff and were ushered into what seemed to be the head office of the building. I was then informed that we were meeting with the Director of the Regional Forest Enterprise Unit and I’d have time to ask him questions if I had any. Whew! Uh, I hadn’t really thought about that one yet and so I didn’t have all that much in store. To be completely honest, I was still wrapping my head around the organizational structure of the state forest management so I felt rather unprepared - as I might say in the States, slightly ‘thrown under the bus’. I started off with several questions about the context of their regional forests - scope, species, etc. Not sure if this visit was solely organized for me, I started to ease into the interview and ask questions that fundamentally addressed the history of the forests in the region. Seeing as how I was speaking through an interpreter to a man who was consistently also answering one of 6 (literally) different phones on his desk, peppered with steady intrusions from other visitors, guests, employees, etc, it soon became clear that without additional questions that were of definite relevance to the regional forest director, I’d reserve my line of questioning for the suite of well informed colleagues that I’d be exploring the forests with later that day. One thing he did share though was that in 2001 Macedonia sold their state telecom company for a sizable sum and used some of these funds to support the purchase of 1 ha of greenhouse space used to propagate forestry trees. They established three different nurseries around the country and have the capacity to produce 12 million seedlings per year. They’ve focused largely on conifers to date including Pinus nigra and Cupressus arizonica but have also begun producing oaks. As a result of their seedling production, country wide they planted 14 million pines last year (about 4000 ha annually with 4000 individuals per hectare). In the Strumitca district they planted 130,000 last year on 80 ha. They usually establish these planted stands on pare land and mainly consist of Pinus nigra, Pinus sylvestre, Abies spp., black locust, Thuja spp. and oaks. In the future they plan to reduce the scope of these plantings to about 10 million per year. While they plant in both autumn and spring, they have an 85% success rate in the fall which is far higher than that of spring plantings. After another 10 minutes or so, we said our thank yous and goodbyes and headed outside to the parking lot where 2 Lada 4x4s were waiting for our party of 8. We set off for our day long field trip, stopping at a cafe on the way for a quick breakfast/coffee stop. Setting some context for the state of the forests in the Republic of Macedonia, 90% of all forests are owned by the state. Of that total, 50% is coppice and 50% high forest. The nation features 30 forest management branches which are divided by their respective watershed boundaries. Each of these districts maintains management plans for between 6 and 20 state forests with the Strumitca district managing about 10,000 hectares divided between six different units. Generally speaking these management units must be 5000 ha or less for high forest and 10,000 ha or less for coppice stands. Each office creates the management plan, the ministry then goes on to approve it and checks to make sure it's been realized or accurately carried out. Macedonia’s climate is dynamic, resting at the confluence of both Mediterranean and continental patterns. While prone to microclimatic variation, the Strumitca region receives about 500 mm precipitation annually with a dry summer - which means up to 5 months with no rain. Here are some statistics about the projected and realized wood yields in Strumitca: Logs - Projected ~ 140,000 m3/yr (2009) Realized - 96,000 (2009) Firewood - Projected - 630,000 m3 (2009) Realized - 460,000 m3 (2009) For local harvest - 130,000 m3/yr About 80% of this total is realized - In this case, trees are marked by state foresters for villagers to cut In Macedonia, coppice management is still recognized as an applied management system. The vast majority (95%) of coppiced wood is sold as firewood. Retain it fetches about 50 Euros ($70) per ‘spatial’ cubic meter (one that’s stacked - the same way we measure stacks of firewood in the States). That’s almost $255 per cord. Beech is about 10-15% cheaper. Fuelwood costs in Macedonia are considerably higher than those of Bulgaria which means they face some competition from the neighboring country. It’s rare to find oak of sawlog quality in Macedonia but when they do produce lumber, they typically export boards to Greece. Generally, species composition varies by elevation and they coppice at basically all of these levels. Beech occupies the highest sites, hornbeam (Carpinus orientalis) and sessile oak at the mid-slopes and pubescent oak at the low elevations. Their primary management challenges come from anthropogenic (human) sources. Extensive overgrazing and selective cutting both reduce stand quality and stool vigor. Often villagers practice selective thinning in coppice stands which is useful if they’re removing low quality stems from individual stools, but if they completely remove all the stems from a stool, it is likely to die as it no longer receives any light to stimulate regrowth. While they do have roe deer, their numbers are controlled by active populations of both hunters and wolves. Our mini convoy headed east, back towards the Bulgarian border. Just a few miles shy, we turned right and began to ascend Belsitsa Mountain - the same ridge that we’d climbed the previous day in Bulgaria. Somewhere between 800-1200’ elevation we stopped to examine some ten year old Sweet Chestnut coppice. Interspersed with an occasional black locust, Pande explained that this stand, like all of the chestnut they manage in Macedonia, is typically cut on a 25 year rotation. We explored a stand 100 ha in size (260 acres) that was actually last cut somewhere between 30-40 years ago. On average, the regrowth was 8-9 meters in height (24-30’), and polewood dbh (diameter at breast height) varied from 4.5” through to 7” with poles of each class found on most stools. There was some variation in the number of stems per stool and the stand lay on a 15-25% grade. Typically it ranged from 5 through 7 with a few stools still possessing as many as 12 healthy stems. Stools were spaced fairly widely - 3-4m centers (10-13’) and they cast a dense shade on the forest floor - about 97% canopy cover. I found an average of 100 ft2 basal area per acre. Pande explained that this was most likely the third generation of resprouts from the trees originally planted here. Reading the growth rings on a remnant stump, during the early years, the pole averaged .1” diameter rings per year, falling to .05 and .02 as the canopy closed towards the 25+ age bracket. In the experience of our guides, these chestnut sprouts don’t start to produce nuts until they’ve reached about 25-30 years in age. At higher elevations, this mountain hosts extensive beech stands (450-500 meters and up). Below that, the chestnut thrives on the relatively moist, cooler north-northwest facing slopes. While this chestnut did show some signs of the blight, it was not nearly affected as dramatically as the stands I saw in Croatia just a few days earlier. It was sunny and pleasant up on the mountain and we took a half an hour or so to explore the stand to get a feel for its structure and scope. Our next stop took us over to the other side of the valley to Ograzhden Mountain - a much more dry, exposed, south-facing mountainside where the beech stands seldom extend below 900 meters elevation (as compare to 450-500 on the other side of the valley).’ We passed through a modest agricultural village on our way up, full of animals, narrow streets, crumbling buildings and lots of character. The intense pressure on the neighboring forest from humans for both fuelwood and grazing lands has long left a scarred, scrubby shrubland in its wake. Here the primary woody species were a very low growing, shrubby, stunted version of the sessile oak (Quercus petraea) and Juniperus oxycedrus, a largely prostrate, prickly evergreen shrub that seems to be a clear indicator of a legacy of overgrazing just about anywhere you go in the world. We increased our distance from the village and the compacted grassy shrubland and began to climb higher up along the mountainside. The density of the trees increased steadily. Partway up the mid elevation slopes, a sizably impressive, well-placed valley dam filled the void along a bench in the slope - it was placed more or less at the keypoint (the point where the cross sectional shape of the valley changes from a convex to concave shape) of this ‘primary’ mountain valley. We stopped the car and took a few minutes to bask in the grandeur of this oasis which provides a high pressure gravity water source to several of the villages below. From this vantage, we could also make out an expansive clear cut on the far slopes of the mountain - a ‘salvage’ cut undertaken to harvest an useful fuelwood remaining after wildfire consumed a vast swath of the landscape a few years ago. Ljupcho our skilled driver and a faculty of forestry member at St. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Macedonia navigated along the rough, washed out road, straddling deep ruts in some of the more extreme stretches. Forest road maintenance is a constant activity. In Macedonia, they devote 3% of the annual State Forest budget to the practice which hardly covers the true costs/needs of this oh so critical infrastructure investment. Within the roughly 10,000 ha of forest in the Strumitca district, they average about 10-12 meters of road length per hectare. Each spring, machine operators use bulldozers to regrade the road and ensure it’s passable for forest workers and log trucks. Given that the Macedonian forest landscape is extremely mountainous, maintenance of access routes embodies the law of entropy - things steadily move from a state of order to disorder and it requires energy investment in order to revive that ordered state. We reached a grassy plateau after about an hour of windy traversion (I’m making up a word - but I like it. It means ‘the act of traversing’) where a modest, deteriorating cabin provided us with a sheltered space to lunch. Built by the local Forest Enterprise Unit, these houses serve as hunting cabins and staging points for the teams of forest workers who work at some of these remote stands. Just prior to us arriving, I was wondering how foresters go about their work with such a long, windy potential commute - the cabin was the key. ‘Rustic’ in character to say the least, it contained a simple woodstove fabricated from a 55 gallon drum, a few beds, kitchen area and some scattered chairs. We set up our lunch outside on a table top and enjoyed more bread, cheese, and sausage. On top of that, a young forest engineer named Georgi generously gifted us all with pints of homemade rackia (schnapps) that we sipped to keep warm in the exposure of a steady mountain wind. Before wrapping up completely, Pande asked me if I’d like to explore the woods and take some measurements. I’d yet to examine any of the Quercus petarea (sessile oak) here in Macedonia, so he and I rushed off into the woods. They typically harvest their oak on rotations somewhere between 45-55 years. Usually occupying dry, rocky, south facing slopes, the oak is much more slow growing that chestnut (25 year rotations) and they’ve found that this is the optimal point at which to harvest - the point at which the current growth increment and the mean growth increment curves intersect. This particular stand was around 20-25 years old. Generally speaking, oaks in and around this area seemed to be spaced between 6-10’, with an average a bit closer to 8-10’. The landscape is very reminiscent of the shrub oak forests of the mid-elevation slopes along the Rocky Mountains as well as the scrub oak forests of California. Here each stool had between 1 and 4 stems that averaged between 25-35’ in height and 5” diameter at breast height (dbh). Canopy cover was dense here as well - about 95.4% but stem density was relatively low - 80 ft2 basal area per acre. For the most part, this was a monocultural stand - we found more diversity in the valleys but these areas tended not to be managed. Not particularly straight and otherwise useless as a timber crop, this coppice oak is essentially a fuelwood-only product. Pande explained that on average, these sessile oak stands yield about 150 m3/ha, 15-17 cm (6-7”) dbh, and 15 meters in height (45-50’) after about 40-50 years regrowth. Their annual growth increment averages between 4-5 m3 per hectare (61.5 ft3/acre). Stands typically feature 1200 stools per hectare, (but it could be anywhere between 800 and 1500 depending on the stand) or 462 stools/acre. This amounts to about 5000 stems (poles) per hectare (1923/acre). Pande and I hopped back into the near full cars that were waiting for us and we proceeded to visit another 10 year old stand of Q. petrea for comparison’s sake. Located on a steep (40%) slope, these stems were 10-15’ high and average between 4 and 7 quality stems per stool which themselves were spaced roughly 8-10’ from one another. Stem dbh averaged about 1.5-1.75 inches, with some as large as 2.25 and 2.5” . With a long, bumpy ride ahead of us back down the mountain, we set off for Strumitca, retracing our steps from earlier in the day. Probably the most potent silvicultural discussion on the way explored the challenges of converting these oak copses into high forest. While the Republic of Macedonia still formally recognizes coppice as a desirable and viable forest management strategy, they still would like to diversify their wood products and develop a more varied mosaic of forest structure to help stabilize soils and build more diversity within the stands. In this area, most of the oak is nearing 55 years of age. With both oak and beech, their ability to vegetatively reproduce (coppice) after cutting drops off significantly beyond 50-60 years of age. (Chestnut, on the other hand, grows from the root collar, and so its shoots actually develop a new root system - it's much more resilient when coppiced and will thereby regrow even at relative maturity.) Thus, they have a large area of land that will soon need some intervention. If they wait much beyond 55 years, it will be too late to see effective coppice regrowth, if instead they choose to wait and/or thin the stand so as to encourage seed dispersal and reproduction and things don’t work out as planned, it will be too late to reestablish coppice. In the end, most of us agreed that it was worth trying to encourage seed produced stands of high forest in patches integrated within the coppice stand. This will help vary the structure and minimize the losses if their efforts at stand reconstruction don’t succeed. We returned to the Forest Enterprise office, dropped off the vehicles, picked up our luggage and headed north to our evening destination - a village near the town of Radovish - our base for the next day. Zdravko had grown up in this town and helped connect us with a local woman who rented rooms in her house. She kindly welcomed us in, showed us our space and made us tea and coffee. Here Pande gave me an invaluable resource - ‘Estimation of the Economical Limits of Wood Production As a Commodity in Low Graded Productive Forests’. A Macedonian study funded by the USDA in the 1970s that sought to quantify the productivity and value of coppice products. Meticulously undertaken, it featured a remarkable quantity of data on 5 different forest types throughout the country. For each community, they had measured stems per hectare, annual growth increment, basal area per hectare and total volume of wood for between 5 and 10 different stands at ages ranging from 20-60 or more years. This will prove to be an incredible asset to us as we develop our chapter on the yields of coppice systems. Someone called a couple of cabs to pick us up outside and bring us to the restaurant where we’d planned to have dinner. As we waited in the cool night air, a clear sky bore familiar constellations, brining me back to the night sky in Vermont. We shared drinks and food until midnight, leaving absolutely overstuffed - the specialty that night (in addition to yet another fabulously fresh tomato-cucumber-olives-white cheese salad) was the local specialty - basically a salmon pizza. I used my placemat to record the insights I drew out from Zdravko about the basic principles of forest access road siting and design. In short: - Identify key areas to reach (stands of greatest valuable/most desirable to access) - Determine the grade change and the horizontal distance between the starting point and the destination - Aim for a 7% incline (10% will work but not ideal, 12% the absolute max) - Optimize the access the roads provide by minimizing total length - ‘Inwale’ roads (slope them in towards the slope) when possible to eliminate the danger of loaded trucks tipping over down hillsides - Include a ditch for water collection on inwaled roads to help minimize downcutting and erosion (and make sure to send it somewhere useful!) Depending on budget/available resources, lay a clean, well compacted gravel base (4-6”), topped with 2” or so of finer material (or just remove topsoil and compact the site subsoil) We took cabs back home with enough time to get a few hours worth of sleep. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed